Aunty May in my life

Miss Maureen Smythb. Dublin 1908, d. Aramoho 1991.

by John Archer, 2022

1. Dublin

My Aunty May, Maureen Smyth, was born in 1908 at Bishops Gate (?), 20km south of central Dublin, and lived there with her father John Smyth, a dairy farmer, her mother Mary Ann (White) and her younger sister Kitty (Kathleen), born in 1910.

The Smyth family, Dublin, 1911.

John, Kitty, May, Mary Ann.

In about 1911 May's father migrated to New Zealand and set up a dairy farm at Omahina, 11 km inland from Waverley, and in 1913 John Smyth’s sister Kathleen Smyth (Aunty Kate), his wife Mary Ann, May and Kitty and Mary Ann’s brother, John White (a bank clerk) joined him, coming out on the steamship Ruahine.

The Ruahine had been built for the Britain to NZ emigrant trade at Dumbarton 4 years previously. It weighed 7000 ton and capable of carrying 4000 ton of cargo at a service speed of 14 knots (26 km/h) She had berths for 520 passengers divided into three classes. Her holds could carry almost 8000 cubic metres of refrigerated cargo on the return voyages.

We had a memento of the voyage on a green card, with the ship’s name and photo, and a list of about 100 passengers.

2. Omahina

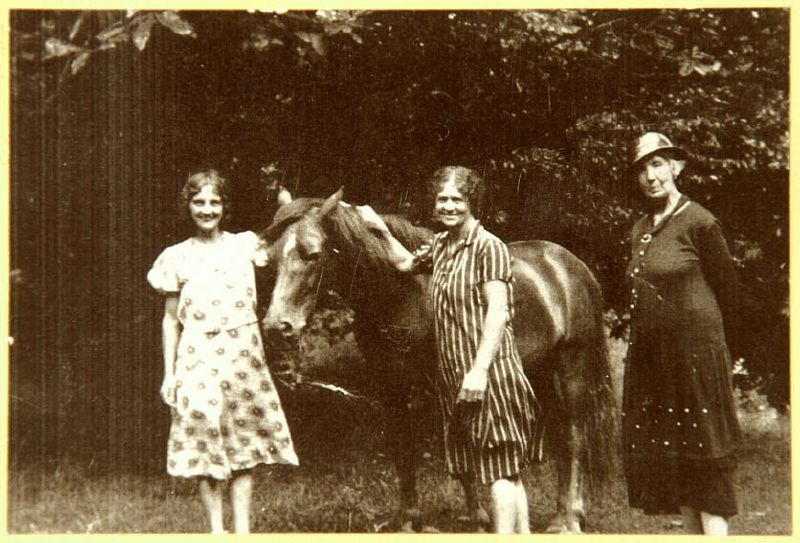

The settlement of Omahina was 11km inland from Waverley, and separated from it by a gorge. It was a growing settlement then, with a school operating from the home of one family (a small school was later built in 1918) and there was a small dairy factory that collected milk for the cheese and butter factory at Waverley.My Aunty Eileen was born in 1915, my mother Breda (Mollie) and twin brother John in 1916, and my Aunty Sheila in 1919. But the Smyth kids did not go to the local school. They rode horseback every day to the convent Catholic school at Waverley. May and Kitty got secondary education as boarders at Sacred Heart College at Wanganui, (“the Convent on the Hill”) with Kitty learning to paint and May learning the piano.

The Smyth family, Omahina, about 1928. They all met in “town” at Tesla Studios to get this taken: most of them riding by horseback and buggy to Waverley, then train to Wanganui, while Uncle Major and Aunty Sis would have been working in town, and would have traveled by tram.

1. John White, my grandmother's

brother (Known as Uncle Major)

2. Eileen Smyth, aged 13, my aunt and 2nd mother.

3. John Smyth - my grandfather

4. Breda (Molly) Smyth - my mother, aged 12.

5. Eileen Smyth (Aunty Sis)- my grandfather's sister.

6. Sheila Smyth, aged 10

7. John (Johnny) Smyth - Molly's twin brother

8. Mary Ann Smyth (Nee White) my Nana .

9. Kathleen (Kitty) Smyth aged 18

10 Maureen (May) Smyth aged 20.

2. Eileen Smyth, aged 13, my aunt and 2nd mother.

3. John Smyth - my grandfather

4. Breda (Molly) Smyth - my mother, aged 12.

5. Eileen Smyth (Aunty Sis)- my grandfather's sister.

6. Sheila Smyth, aged 10

7. John (Johnny) Smyth - Molly's twin brother

8. Mary Ann Smyth (Nee White) my Nana .

9. Kathleen (Kitty) Smyth aged 18

10 Maureen (May) Smyth aged 20.

Then the Great Depression came, and there was no money for the others to go to boarding school. A window got broken in the house, and for a year the hole was covered only by a sugar-bag.

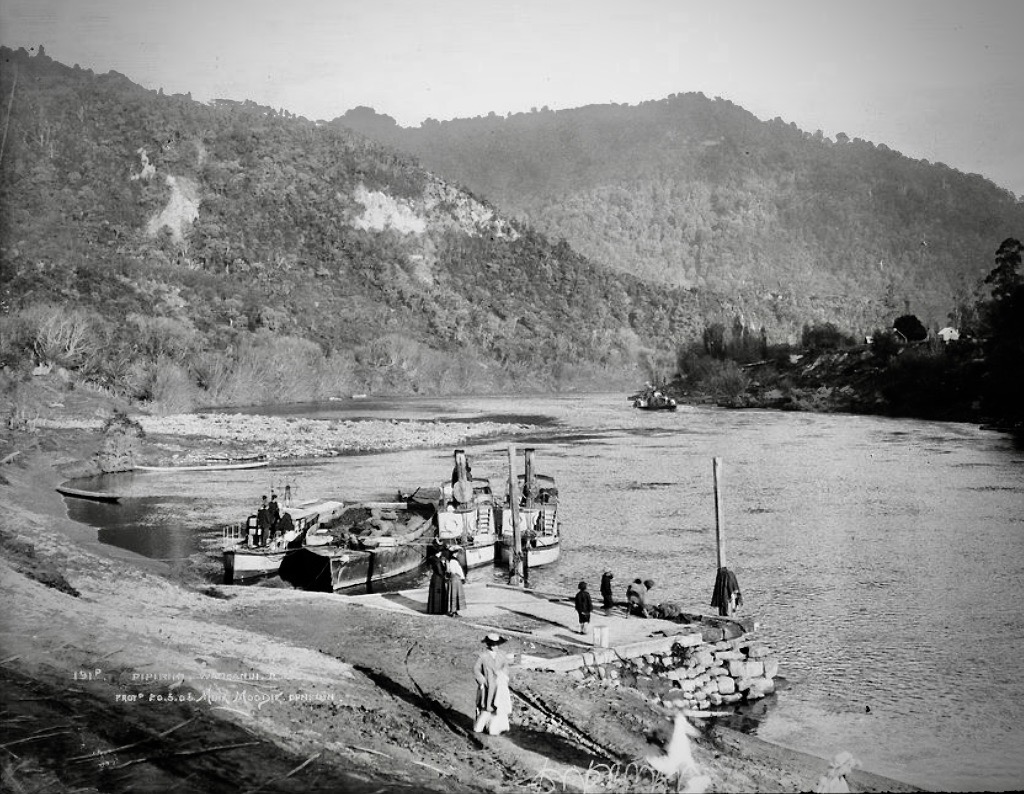

3. Up the Wanganui River

In 1928 May had become a home-schooling teacher (‘a governess’) for the children of the Davey family, who were farming up on the hill behind the Maori village of Jerusalem halfway up the Whanganui River. There was a school at Jerusalem, but all the teaching was in Maori. There was no road to Jerusalem. “It took seven hours to get to Jerusalem on Hatrick's boat,” she told me.

Arriving at Pipiriki

Aunty May with the Davey children

at Jerusalem.

Rear. Mr Davey, Joyce, May, Father........?

Front. ..........? ............? Mrs Davey, Violet.

Rear. Mr Davey, Joyce, May, Father........?

Front. ..........? ............? Mrs Davey, Violet.

May and Mrs Davey

"Princess Diana." May on Brownie in Davey's cherry orchard

Aunty May (left) and friend with a lamb, in front of Sister

Suzanne Aubert's convent down at

Jerusalem

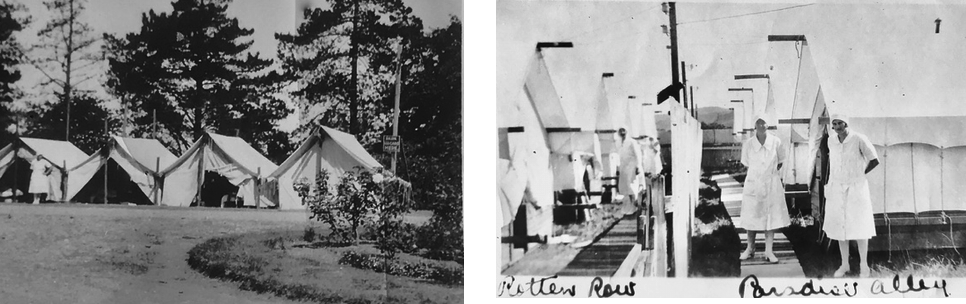

Nurse's accommodation and hospital

wards.

When Eileen finished school in about 1930, she joined the Country

Women’s Institute, became friends with another teenager, Cora

Archer, whose parents Maggie and Bert Archer owned the Mangamahu

Hotel, and got a job there as housemaid and assistant cook.4. Twenty-four Paterson Street

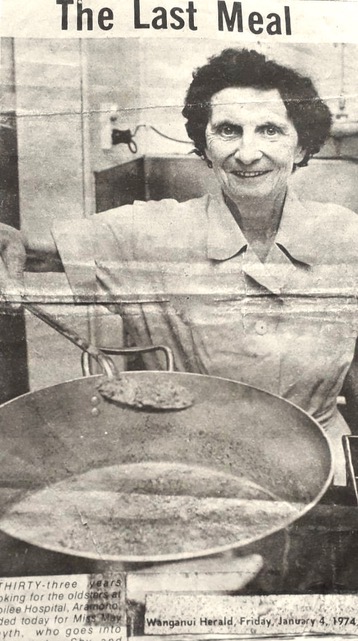

In 1937, May’s father died prematurely (depression and alcohol) and there were no jobs for the girls at Omahina. The family took out a mortgage on a farmlet on the edge of Wanganui, at 24 Paterson Street, Aramoho. To pay for it, 29-year-old May got a job in Wanganui, then in 1940 as a cook 2 km away at the Jubilee Home, a geriatric hospital, while 21-year-old Johnny, my mother’s twin, remained in the Waverley district as a farmhand, 27-year-old Kitty was nursing at Palmerston North Hospital, 18-year-old Sheila lived at Paterson Street, and walked half a kilometre to Somme Parade to catch the tram to town to J. J. McKaskie’s oilskin raincoat factory on Taupo Quay, and 29-year-old Eileen was working at the Mangamahu Hotel.May soon became the chief cook at Jubilee, biking to and from work every day until she retired in 1974. A wicker basket in front of her bike’s handle-bars carried home scraps of meat, and all the neighbourhood cats gathered by the green mailbox at quarter past five, Wednesday to Sunday, waiting to be fed.

When war broke out in 1939, Johnny was conscripted and sent to Egypt as an infantryman, fighting in the front lines for 5 years, driving back the Germans all the way from Suez to Tobruk, then across the Mediterranean to Italy, to Monte Cassino, and to the River Po. He was often sent out at night with just a couple of others to patrol no-mans-land, was wounded three times, the last time suffering ‘shell-shock’ (post-traumatic stress disorder) and was hospitalised for many months after the war ended.

5. The Mangamahu Hotel

When my very pretty 22-year-old mother, Molly, went to visit Eileen at Mangamahu in the late 1930s, Maggie’s son Dave, who was driving one of his dad’s trucks, fell in love with her. Before long they were married, and I was born in 1941.

Dad was conscripted not long afterwards and sent to guard Fiji from Japanese attack. He did not come home again until 1945, and my war-time pre-school years were spent between the kitchen and back yard of the hotel and the house and garden of Paterson St.

My early memories in the kitchen of the Mangamahu hotel were Gran’ma and Aunty Eileen cooking and cleaning for the guests, mostly Mrs Tansy (Teacher Tan) and council roadman Frank Purcell ('Uncle Frank'). Grandad tended the bar, grew all our veges in a big garden behind the hotel, ran a small farm which for obvious reasons was called Snake Gully (although Soho was stencilled on the wool bales), killed a hogget every week for meat, and managed the hotel’s three truck-drivers. Back in 1919 he had bought a small solid-tyred, chain-driven truck to bring out barrels of beer. It was soon taking back bales of wool, requiring another truck, then another….

At Paterson Street, Aunty May spoilt me rotten. She was such a good cook, and she played songs on the piano for me, showed me her prized roses and picked cherry-plums for me.

Not long after WW2 ended, Maggie Archer, my Gran’ma died, and my grandad sold the hotel so he could retire to his farm at Soho, spending most of his 60s and 70s cutting scrub, growing veggies, sending out invoices for the farm transport work, and tending his sheep. The new young school teacher, Barbara McGlade, was boarding at the hotel, so mum and dad rented the school house and we lived there from about 1947 to 1950.

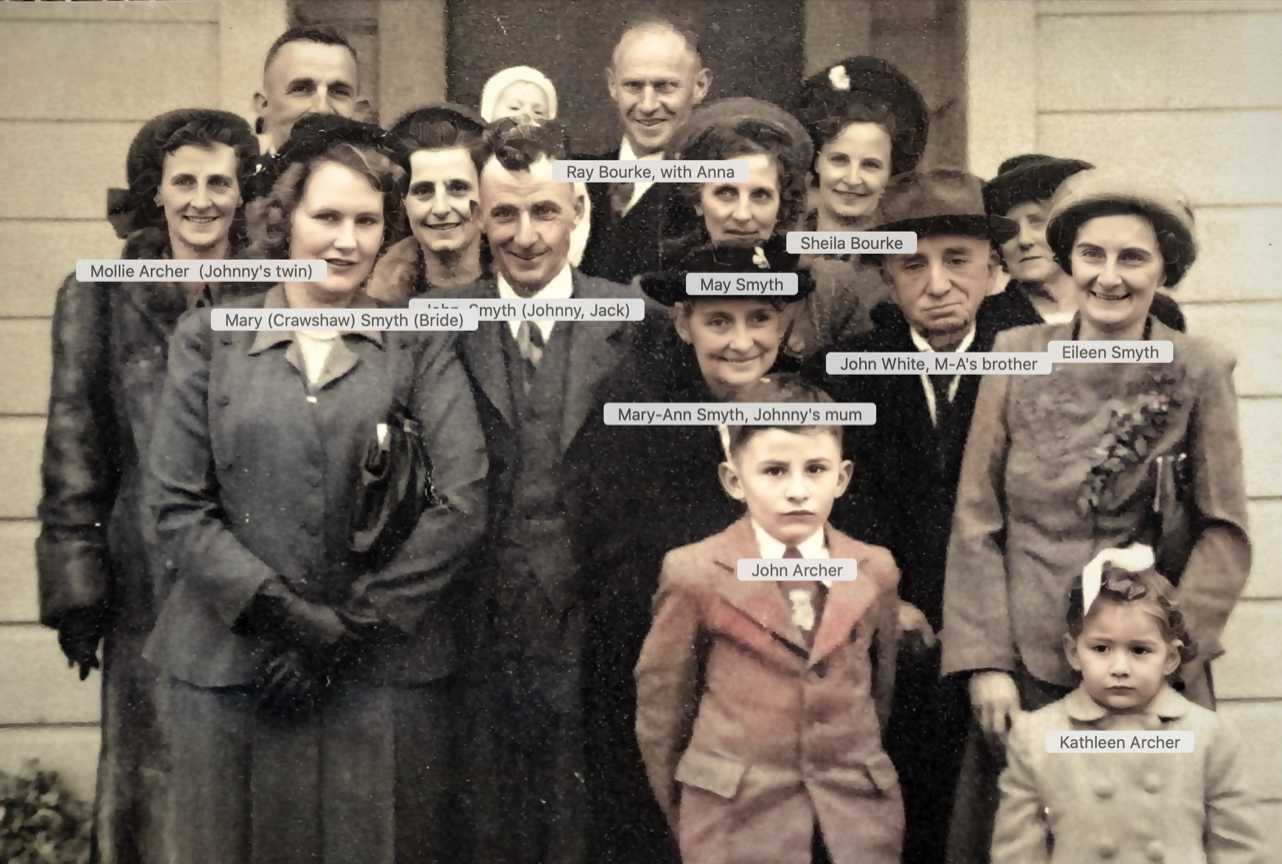

My Nana, Mary Ann Smyth, died in her sleep at Paterson St in 1950, and was buried beside her husband in Waverley Cemetery. Then Sheila married Ray Bourke, a farmer at Rangiwahia, and Johnny married Mary Crawshaw, his old Waverley sweetheart.

Mary and Johnny's wedding

6. The house at 24 Paterson Street

Eileen and Kitty joined May and my Nana’s brother at Paterson St. It was a small 2-bedroom house. In one bedroom was John White, Uncle “Major” (he dressed very formally) now very old, while in other bedroom Eileen and May slept in the double bed, and Kitty slept in Nana Mary Ann’s single bed.There was a tiny kitchen with a coal range, a gas oven, and a table where they ate most meals, next to a dining room/living room with an open fire, three comfy old armchairs, and an elegant matching sideboard, table and chairs, reminders of their well-off 1920s dairy farm days. Most evenings were spent around the fire in there. Each evening Aunty May would carefully fetch one of the apples from the boxes under the tank-stand, cut it into quarters, remove the core and share it around. Then she would make us all a cup of tea with a home-baked biscuit on each saucer. At eight-o-clock we all knelt down to say the Rosary and three Hail Marys for Blessed Oliver Plunket. The only time the formal dining table was used was on Christmas Day and Easter Sunday.

For Christmas and Easter, the dining room was decorated with spiraling crepe paper streamers radiating from the central light fitting, and everyone turned up at Paterson St to squeeze up around the table for a traditional British Christmas dinner, including Aunty Eileen’s freshly dug new potatoes and freshly picked new season’s peas, May’s plum pudding with thruppences and a thimble, topped with fresh cream from their cows, and her Christmas cake with about a kilo of dried fruit, a dozen eggs from her chooks and about centimetre of icing: almond icing underneath and elaborately decorated white icing on top. Easter Sunday was similar.

At the rear of the house was a washhouse with a gas-heated copper and two concrete tubs with a hand-turned wringer between them. Outside the back door, a corrugated-iron water tank stood on a tank-stand with boxes of last autumn's apples stored underneath it, the outside flush lavatory next to it and the wood-shed/bike-shed opposite. In the shade beyond the shed was the meat-safe for keeping meat, butter and milk fresh. Beyond that was a dugout from 1943 Japanese bomb-scare days.

There was also a formal sitting room with a fancy fireplace, floral wallpaper, floral carpet, floral armchairs, a wind-up gramophone, a piano and a tea-trolley with fancy tea-cups for “entertaining visitors;” relics from the 1920s when ladies visited each other for “afternoon teas.”

7. Boarding with my aunties

That sitting room was largely unused until I came in from Mangamahu’s one-room school in 1953 to go to “the Brothers” school, and for the following five years to the Marist Fathers boys college.An armchair was pulled away from the wall of the sitting room, and a bed was made up behind it for me. Every school morning for the next six years, Aunty May would wake me up with a hot cup of well-sugared tea, made from the kettle boiled on top of the gas stove. There was only one electric plug fitting in the whole house, so the plug for the big valve wireless had to be pulled out to make toast for breakfast on the electric toaster, a non-automatic, non-pop-up one.

Except on Mondays and Tuesdays, her days off, May would be leaving for work as I came into the kitchen for breakfast. My school lunch would be neatly wrapped thick mutton sandwiches, with an orange or home-grown apple, and for 10:30 am play-lunch, a home-made afghan or melting moment biscuit made by Aunty Eileen and a slice of chocolate cake or fruit cake that May had brought back from the huge slabs she made in the kitchen at the Jubilee Home.

On Mondays, May and Eileen would boil up the gas-fired copper and then boil, rinse, wring, hang out, bring in, iron and fold the bedding and dirty clothes, and on Tuesday May would go shopping with Eileen at Aramoho or to the mid-city shops in Victoria Avenue.

Eileen would start up the 1931 Model A Ford that their rich Aunt Bridey had bought for them 20 years previously when she came out from Ireland to visit them. In winter the car sometimes had to be crank-started.

The car had been sold to them in New Plymouth. Seventeen-year-old Eileen was taken from Omahina by horse and gig to the Waverley railway station, rode the morning train to New Plymouth, walked to the Ford car place, was given a basic driving lesson, drove the car 125 km back in the afternoon, on the bumpy gravel roads, and at the end of a long, tiring day, she arrived safely home again. Several times she told me “I had to drive across the Omahina Gorge to get the car home!” It was a major achievement.

Aunty May usually went to work on Saturday and Sunday because some of the other cooks had children to care for on the weekends. There were about 2000 church-going Catholics and 9 Catholic priests in 1950s Wanganui, so we rarely went to the 8.30am Sunday Mass at Aramoho, or to the wonderfully elaborate 10am High Mass 5 km away at the big church right in the middle of the city, with its rhythmic Latin responses and pipe organ and Gregorian chant and incense, its burnished candelabras and masses of flowers and half a dozen robed celebrants at the altar with white lace or gold-embroidered robes.

So at six-o-clock every Sunday morning, May woke us with cups of tea, and we dressed up in our best woollen clothes; Kitty in orange brown, May in blue, Eileen in pale brown, and me in my blue St Augustines blazer, white shirt, school tie and grey longs.

At a quarter past six we drove off to the half past six Mass at the big church in town, all in hurried mumbled Latin with no singing or grand ceremony. It was cold in winter. By 7.30 we were back at Paterson Street.

By 10 to eight, May had changed, eaten breakfast and biked off to work at Jubilee Home, while Eileen had headed off to hand-milk the 3 cows and separate the milk to get the cream for sale, and Kitty started the half kilometre walk to Somme Parade to catch the tram back into town to Belverdale Hospital.

8. Living off the land

Aunty May earned almost £5 a week for her work at Jubilee, paid to her in a little brown-paper bag with notes, silver and copper coins. Aunty Kitty ('Sister Smyth') probably earned about $7 a week, and Eileen got a free pound of butter and a few shillings for the cream that she sold. Blackberry bushes were beginning to spread across the cow paddock on the hill above them, and in midsummer they picked bucketfuls of juicy ripe blackberries, made jam from a few of them and sold the rest to the greengrocer at the Aramoho shopping centre. They picked red currants and gooseberries and made jam from them also. In early summer May and Eileen picked bucketfuls of cherry plums and preserved them in quart-sized Agee jars, and in late summer they bought cases of Golden Queen peaches from greengrocer at Aramoho and peeled, stewed and stored them away in the big kitchen cupboard too.

On

Friday nights I changed out of my school uniform (grey

woollen shorts and grey cotton shirt), put on my white

shirt, school tie, blue blazer and grey woollen longs and caught the

bus (thruppence) into town. (The

electric trams (tuppence) had been running since 1908, but

their tracks were pulled up in 1952)

On

Friday nights I changed out of my school uniform (grey

woollen shorts and grey cotton shirt), put on my white

shirt, school tie, blue blazer and grey woollen longs and caught the

bus (thruppence) into town. (The

electric trams (tuppence) had been running since 1908, but

their tracks were pulled up in 1952) I got off halfway down Victoria Avenue and first went to the splendid 7.30 Benediction service at St Mary’s, then at 8pm to the pictures at Majestic Theatre right next to St Mary’s.

Aunty May had given me half a crown (2 shillings and 6 pence or 2/6 or 30 pence). That was sixpence (6d) for two bus fares, 1/6 for an upstairs seat, and 3d for a chocolate-dipped ice-cream at half time, and sometimes I got a packet of Jaffas too. I caught the bus home after the main feature finished at 10.30pm ,and the half kilometre walk home 11pm, with the high tension power lines crackling overhead on frosty winter nights, was a bit scary.

9. My aunties' social life

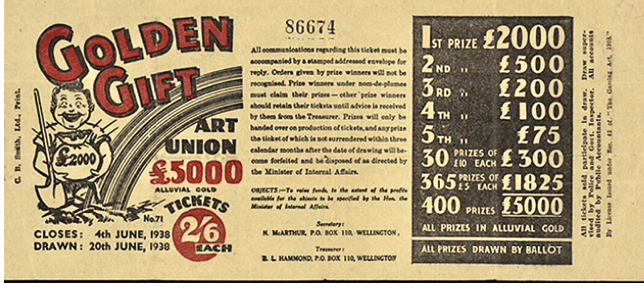

My three unmarried aunties never went away on holidays anywhere, but they read a lot of newspapers. The paper-boy tossed the Wanganui Herald (tuppence) over the front gate every evening, every Tuesday they bought the weekly Listener and the Truth at a book shop , and on Sunday the Tablet at the church door and the Sports Post (for me to read all the cartoon strips in it) at the dairy on the way home after Mass. In the evenings they read those papers, and in their spare daylight time they were kept happily occupied with their cows, their cow paddock (mainly getting rid of ragwort, sprinkling one pinch of sodium chlorate on every plant in those pre-hormone spray days), their veggie and flower gardens, their orchard, their cooking and preserving, and religiously buying, wrapping and sending presents with elaborate birthday, Christmas or Easter cards to their many nieces and nephews.May belonged to the local Rose Society

when

she was younger, but because she was working on the weekends, that

petered out. Having had a very horsey childhood, Eileen went to race

meetings in her early days, putting “ten shillings each way” on the

favourite horse, and when I was with them in the 1950s they bought

an “Art Union” ticket for 2/6 each week, checking winning numbers in

the evening Wanganui Herald when it was drawn, and occasionally

winning £5 or even £10. Their social life was centred on Catholic

school fundraising fairs (Catholic

schools were self-supporting in the 1950s) They stood

around the quick-fire Spinning Jenny: click-click-click…. c l i c k

….Click!

when

she was younger, but because she was working on the weekends, that

petered out. Having had a very horsey childhood, Eileen went to race

meetings in her early days, putting “ten shillings each way” on the

favourite horse, and when I was with them in the 1950s they bought

an “Art Union” ticket for 2/6 each week, checking winning numbers in

the evening Wanganui Herald when it was drawn, and occasionally

winning £5 or even £10. Their social life was centred on Catholic

school fundraising fairs (Catholic

schools were self-supporting in the 1950s) They stood

around the quick-fire Spinning Jenny: click-click-click…. c l i c k

….Click!until they had won a chicken or a bottle of wine, they chatted to all their church friends and wrote their names and phone number (38 168) next to numbers in lots of raffle note-books, bought cups of tea (with proper saucers) together with scones that were properly topped with whipped cream and a dab of raspberry jam, and drove home happy.

The Prefect and my parents'

Triumph at 24 Paterson St

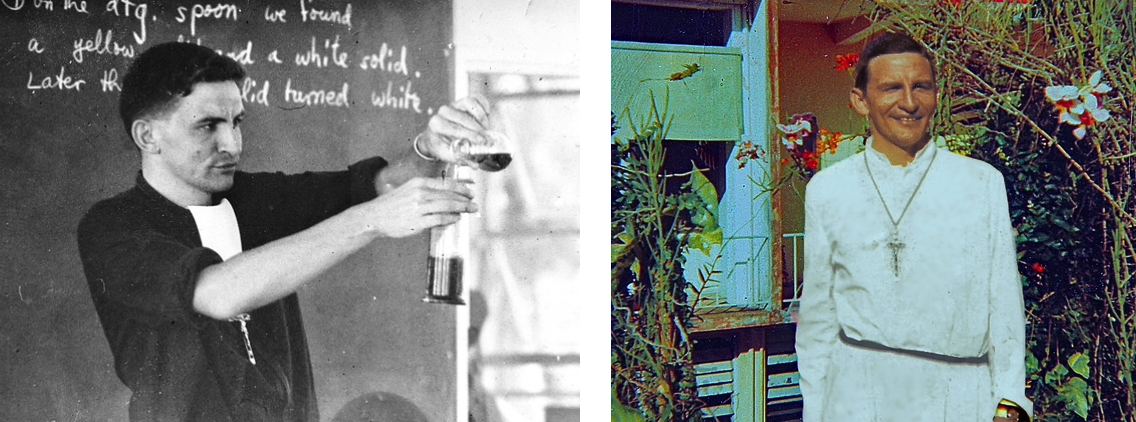

10. The Marist Brothers

In 1958, at the end of 5 years at St Augustine’s College, I was asked if I would like to “try a vocation” as a Marist Brother. It meant living a life of celibacy, and living in common without being paid, but our Church needed volunteers as teachers, and there was no government money to pay teachers in Catholic school back then. Early in 1959 an ex-WW2 DC3 flew me to Timaru and I settled into life as a postulant at the rural novitiate there. At Easter, Aunty May sent me a huge fruit cake, elaborately decorated with “Happy Easter.” A similar cake arrived for my birthday in June “Happy Birthday,” then when I became a novice in September and also at Christmas. These cakes continued to arrive regularly for the next five years of my training.But when I started teaching, I didn’t see much of May, Eileen and Kitty, because the Marist Brothers schools I taught in were far, far away from home. I was continually being moved to new schools by my superiors to fill gaps. It was very unsettling.

11. Palmerston North

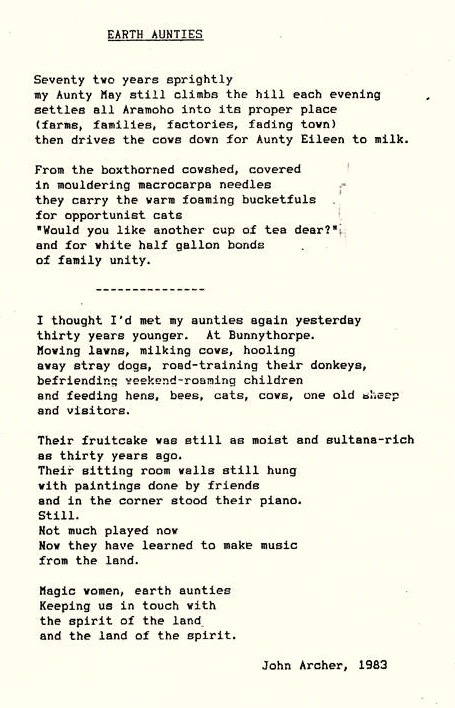

In 1979, after 15 years of this high-pressure teaching, I left the Brothers, and I got a lovely peaceful, stable job as a botany technician at Massey university in Palmerston North, and I could visit my aunts regularly. Aunty May had retired at the end of 1973, Aunty Kit had been paralysed by a stroke, and the other two were caring for her. May had retired from Jubilee, but was fit as a fiddle, enjoying life gardening, baking cakes, preserving, fetching the cows, milking, and giving any visitors cakes, preserved fruit and half-gallon beer flagons full of fresh milk.

After working for nothing in the Brothers for many years, I was 40 years old with no savings. I had rented a flat in Palmerston North for $30 a week, and out of my salary of about $6000 a year after tax, I had managed to save $5000 by the end of two years.

House prices averaged $35,000 in Palmy in the early Muldoon years, and I was warned that high inflation rates would soon send prices spiraling. Mum and Dad gave me $2000 and May and Eileen gave me another $2000. I now had $9000 in my account. On my salary, the BNZ could lend no more than $20,000, so I had $29,000 to buy a house. There was a run-down but solid 3-bedroom ex-state house at the end of a cul-de-sac with an asking price of $30,000, and out of the blue Aunty May sent me another thousand. So by 1982 I had my own home!

I took 2 boarders into the other bedrooms and the mortgage was paid off in 7 years, by which time Muldoon's 15% annual inflation rate had raised the average house price in Palmerston North to almost $100,000. I had been able to buy a house just in time, thanks to the kindness and generosity of Aunty May. (and Aunty Eileen and my parents)

After 20 peripatetic years, I finally had a stable job and a stable home! It was wonderful for my peace of mind.

12. Dementia

But in these same years Aunty May was losing her peace of mind. It was due to Lewey Body dementia. Still physically very fit, she would wake several times during the night, then get up and make Aunty Eileen a cup of tea. Several times during the day, she would walk 100 metres down to the old green letter box to check for mail, or she would sit in her old chair in the living room, frown, clutch her skirt and . . .|

|

By 1988 all this was too much for Eileen. May was taken to the hospital wing of the Jubilee Home and strapped to a bed where she cried all day. She was there for three years before she died in April 1991, aged 83. Eileen also got affected by the same disease and died at Jubilee in 2009, aged 87.

We wondered a lot about the baby. There had been many nephews and nieces brought to Paterson Street over the years. But Aunty Sheila had apparently once mentioned that May had gone away to Auckland for six months 'to do a typing course' and there was a rumour she had given birth to a baby boy while there. But for the sake of her other sister's good reputations, they had all decided to forget it ever happened...until May forgot to forget. I often wondered about the aging man in Auckland who was my cousin.