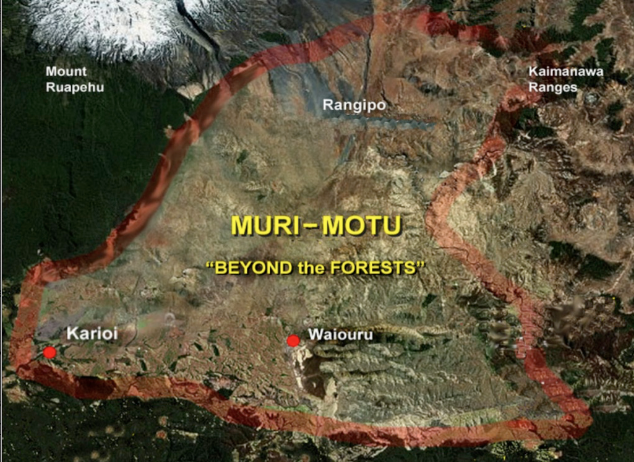

Waiouru in Ancient Times

1.

Waiouru is on the Murimotu plains

For Polynesians north of us, mo-tu ("where it's rising")

were islands rising up from the sea. Sailors could seek

shelter there. So in Aotearoa, patches of forest rising up

from bare land also became known as motu, where travellers

could find shelter and firewood. But the tussock and desert

lands around Waiouru were "muri motu," beyond the forests.

Coast-to-coast travellers could walk across them very

easily, but there was little shelter if the weather turned

cold and wet.

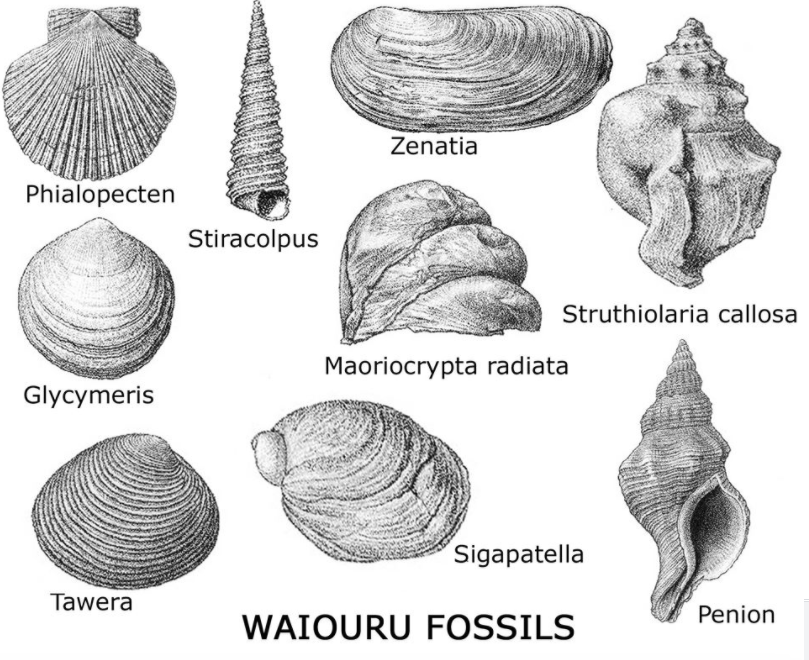

2. When Murimotu was under the

sea

The

Murimotu plains were once under the sea. You can find about

25 different shellfish in the old seabeds that make up the

hills behind Waiouru. Here are some of the more common ones.

When you find one, look the name up in Google to discover

the age of the layer of hillside that you found it in.

By

identifying

the fossils that they find in a layer formed by an old

seabed, Geologists can tell when and where the layer was

formed. If you are still at Waiouru, happy hunting.

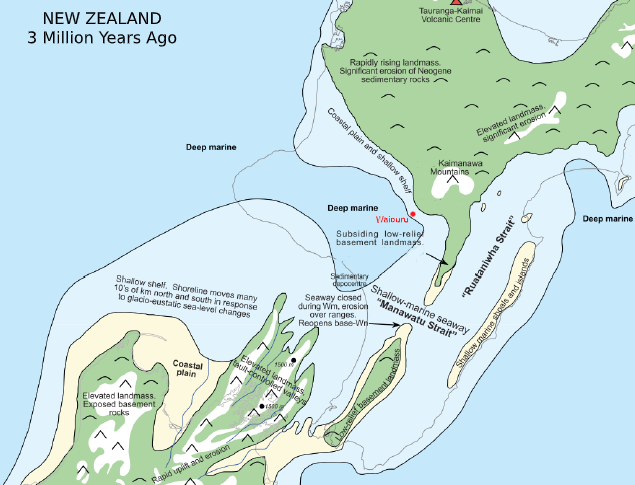

Between

200

to 150 million years ago mud and fine sand was carried down

rivers and into a deep sea bed and hardened to form

greywacke rock. That's the rock in the narrow gorges of the

Moawhango River.

Then between 70 to 50 million years ago, rivers flowing into

the sea from the Tararua Ranges deposited mud on top of this

to create mudstone, forming the soils in the lower cliffs of

Home Valley.

About 6 million years ago, sea beds around the New Zealand

landmass became shallower, and the resulting shallow coastal

waters in the Waiouru area supported enough shellfish to

produce calcium carbonate skeletons, the sea-shells you find

on the hillsides.

The

Whanganui Basin then became deeper once again, and rivers

from the Kaimai Ranges deposited mica sediments on top of

the sea shell layer.

Finally, about 3 million years ago, this filled-in coastal

basin began to be lifted up again.

Today Waiouru is 900 metres above sea level, lifted up by

the Pacific plate of the Earth's crust sliding under the

Australian plate, pushing it up and creating lots of

earthquakes and volcanic eruptions while doing so.

Mt Ruapehu erupts about one year in every 25 years.

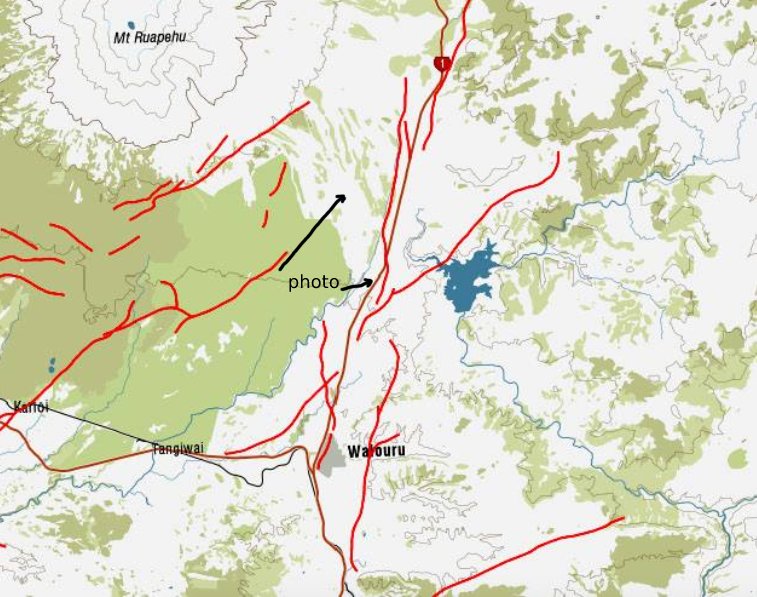

3. Murimotu's earthquake fault lines

Big

quakes have also shaped the Waiouru hills. The GNS Science

website map gives the red lines below as "active

faultlines," although they move only once every 2000

years or so.

The faultline running up the western side of the long

straight on the Desert Road (brown line) is the most

obvious one today. When you drive up the hill past the

entrance to Lake Mowhango, you are going up that fault

line.

4. Lahars have formed the plains around the

volcanoes

Lahars

have

createded the Murimotu plains west of

Waiouru. Water collects in the Ruapehu

crater lake from rain and melting snow,

and when the mountain erupts, or when the

lake's ice wall melts, a muddy flow pours

down the mountainside. There have been

hundreds of small lahars in the last

thousand years, but carbon dating shows

that the river flats lower down the

Whangaehu River were built up to their

present levels by mega-lahars coming past

Waiouru during periods of global warming.

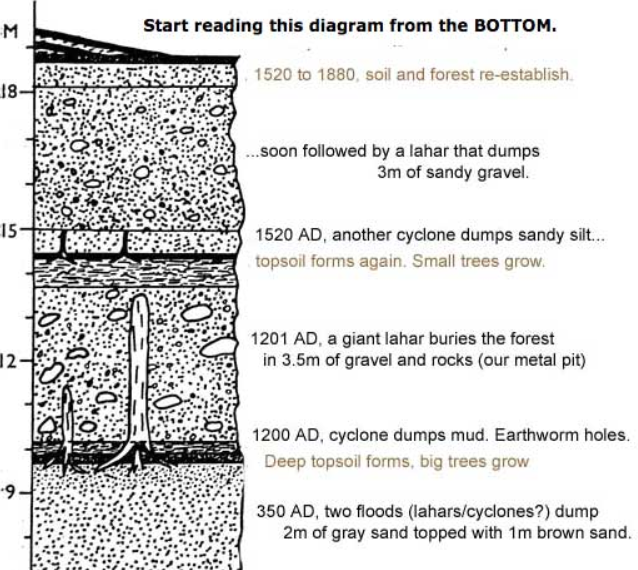

In

about 350 AD lahars dumped 3 metres of

volcanic sand on top of the white pumice

from the Taupo, and forests grew on them

for almost 900 years; big totara

trees were growing on the river flats of

the Whangaehu river valley.

Then came the "Medieval Maximum," the

warmest period in 2000 years: Greenland

and New Zealand both underwent large-scale

colonisation as a result (from Denmark and

Polynesia). The raised temperatures

evaporated lots of extra water out of the

Pacific Ocean, spawning a cyclone that

dumped water on Ruapehu and on the

Whangaehu hills, producing a flood that

left silt all through the floor of the 900

year old forest.

The

silt had only just dried out when,

weakened by the cyclone, the wall of

Ruapehu's crater lake broke, releasing an

enormous lahar that buried the forest in a

3 metre layer of gravel and rocks, topped

by a metre of silt, and smashed off the

tops of the totara trees. From about 1890

to 1960, this gravel layer was dug out for

metalling the clay roads in the Whangaehu

valley where I spent my childhood, and I

saw several of these battered tree trunks.

For the next 300 years, (15 metre level)

the forest started to re-establish itself

while ice built up on Ruapehu during a

chilly, dry period.

Then around 1520, the Earth abruptly

warmed up again for 50 years, and the

flood from yet another cyclone choked the

scrub with half a metre of sandy silt . .

. .

. . . . and not long after, the crater

lake burst again, creating one more huge

lahar that dumped yet another 3 metres of

sandy gravel on the flats. It would have

ruined any Ngati Awa kumara crops on them.

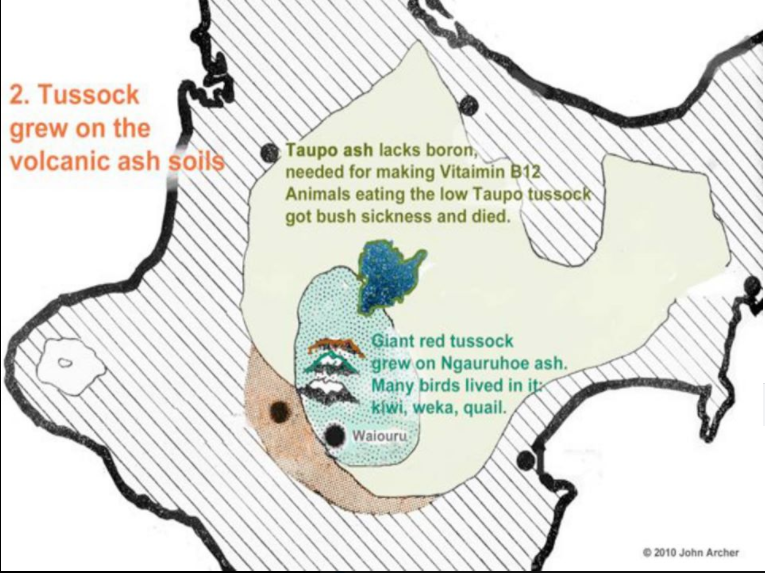

5.

Murimotu's volcanic soils.

Waiouru

sits on a layer of dark volcanic ash recently

deposited by Mt Ngauruhoe. Just below it is a

shallow layer of white pumice with burnt logs in

it from the vast Taupo eruption in 183 AD. The

white pumice ash was about 1000 deg C and moving

at about 600kph. Beneath the white Taupo pumice is

rich brown ash soil laid down by an eruption from

Mt Tongariro in about 8000 BC. This rich brown

Tongariro ash is still the top layer for Karioi,

Ohakune, Raetihi; hence all the carrot growing in

this district.

You can identify these different layers when you

see them in road cuttings, ditches or gunpits.

These eruptions, and the different growth on each

of the soils they laid down, play a big part in

the stories of human settlement that follow.

6.

Birds on the Murimotu plains

The Ngauruhoe ash north of Waiouru was quickly

covered by giant red tussock which provided Moa

with leaves to graze on, and smaller

ground-walking birds like Kiwi,

Weka, tiny

Matuhi, and Koreke

(NZ quail)

with seeds, insects and worms, as well as tunnels

to shelter them from Eagles, Hawks,

rain, wind and snow.

Flying up from the Taranaki coast, Tītī

(mutton birds) dug tunnels (rua-titi) where they

could lay eggs and raise chicks, safe from

predatory hawks and gulls on the seashore. They

made many trips up from the sea with

bellies full of fish,

and the nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium in

their excretions stimulated plant growth.

Where patches of forests had survived the

nuclear-explosion-scale blast from Taupo, there

were Kakapo, Kereru

and Tui. But how many of these

birds have you seen or heard here? When Europeans

came, they brought large rats, dogs and stoats

that killed most of those birds.

Next

7.

Settlers arrive from Polynesia

|