WATTIE

PAIRMAN

There was always only two of us in the contracts.

The first one was Reg Buckley, who worked with me

for about two years, then Wattie Pairman, who was my

mate for about three years. Wattie was a First World

War Gallipoli veteran, quite a character, a good

chap, educated, who rather liked his alcohol,

especially the hard stuff. He liked a little dry

humour in his jokes. He had one year with me on

Polson's station and two years on Collins'.

We were camped out the back and were working on a

ridge above the camp, sawing a long dead totara for

posts and battens. The tree was half buried in the

ground, and we had to dig a trench on one side so we

could manipulate the crosscut saw. Then while we

were sawing off lengths of posts, one we had just

sawn through dropped down with a great bump. Wattie

was on the trench side when this happened. As the

opposite end tipped and started to move, Wattie

ducked down deep enough to avoid being crushed: The

log rolled over the top of my mate and set sail for

the bottom of the gully. The log pushed him down a

little, but no harm done.

He stood up and watched it roll, then to go end over

end, until it went clean through the bunk tent. The

log missed the tent pole, came through and hit the

foot end of my bed, smashing it into the ground.

That turned out to be a wonderful joke for Wattie

but all the tent and gear belonged to me. The log

had bounced from my bed, smashed into a box of

stores, mainly flour and sugar, then came to rest In

the creek. We lost a day cleaning up and sewing up

the tent damage; sugar and flour was scattered

around everywhere. This happened on one of our last

jobs for Polson's, just before we had to pack all

our camping gear over to Collins Brothers at Aranui

Station.

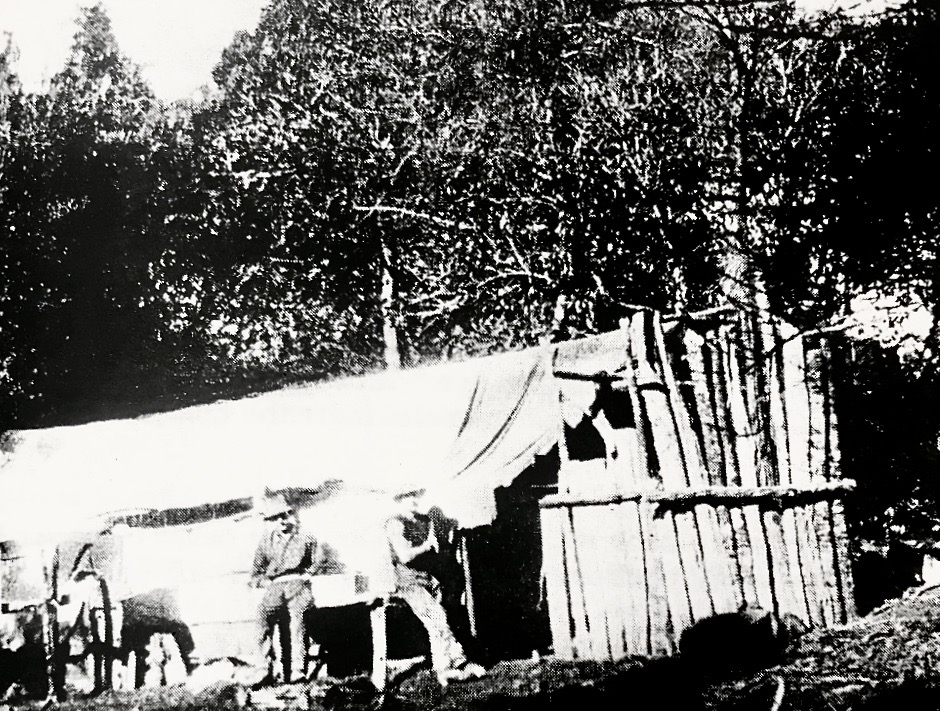

SETTING UP CAMP

We had to repack the next day, load the packhorses

and proceed to the back of that station, where we

had to put up a reasonably good camp, for we had

quite a large amount of work to do in that vicinity.

It took almost three days work.

First we had to find a place where good clean water

was handy and where there was plenty of wood handy

for the camp-fire. We had to find straight poles

from the bush for tent poles, as well as split wide

slabs for the fireplace. We made a frame to nail or

wire the slabs on, making a little wall about eight

foot long and about ten foot high, with a three-post

wall at right angles at each end. Then we built up

clay inside about two foot six high. This left a

place like a shelf to put the camp oven and billies

on while doing the cooking. and we put in big nails

on the slabs to hang out wet clothes to dry.

We always had a pole frame inside the tent to keep

it intact in windy weather. The bottom of the tent

was usually tied down to pegs, and logs were placed

around to keep the cold draught out. The tent that

went over the pole frame was made of calico, with a

tent fly of calico above it to stop the spray from

the rain going onto the tent. Once in a while when a

gale was on, we had to go out in nightshirts to make

things a bit safer. Or when the gale finished we got

at it with needle and thread to mend the holes. When

camping in the bush we did have a tree branch break

off occasionally and fall on the tent.

The beds were made of poles but with us it was not

manuka. Because the bush was usually handy, we

selected good straight poles and softer timber that

was easier to staple the sacking onto. We never

selected forked trees, we drove four stout pegs Into

the ground for bed posts. Bracken fern was good with

canvas thrown over the top beneath the blankets.

CAMP FURNITURE

Most things necessary were split from straight trees

into thin slabs. We usually had staple boxes or sawn

off bits of trees which were about one foot through

to sit on. Candles were the mainstay for lighting

but we often nursed a kerosene hurricane lamp from

camp to camp which was useful for going for water at

the spring or creek.

If one felt uncomfortable, the lantern was

particularly handy for finding one's way away. Most

places we didn't need a lavatory, we usually walked

about three or four chain from the camp and squatted

amongst some shrubbery on the off windward side of

the camp. Some places we dug a deep hole, put a

stake each side then put a pole across for us to

rest on over the drop.

There was only enough room to hang clothes from the

framework inside, and to keep things in a box or two

under the bed. Of course you often put your best

trousers under the homemade mattress to hold the

creases right.

CAMP FOOD

It was never too wet to go pig-hunting to bring home

some pork, or to down a kaka from a high tree-top.

They made a wonderful tasty stew. Of course if there

was something special on somewhere we might go, but

usually we were often weeks on end, only walking out

to the homestead once in a while. I stayed on one

place working for four months.

The cowboy (the sheep-station's 15 year old

cow-milker) brought our mail every fortnight and

sometimes through the week. I

always looked forward to the Auckland Weekly to

read, especially on Sunday if we were not working.

Woods

Great Peppermint Cure was great. . . Still

going I think.

Our mutton or beef killed on the

station was the mainstay for meat and the price

twopence halfpenny a pound they charged us. This was

taken off our wages when we were squared up, usually

when we were going to the city for a break after a

long spell of work. I hardly ever worried about the

grog but was known to have got silly once or twice.

I earned a fair sort of cheque at that time.

sCAMP COOKING

We mainly relied on camp ovens for baking our bread

twice a week. We replenished our own yeast with

potato water, and in the summer when the weather was

hot we tied the cork down in the bottle to keep it

airtight. Sometimes the corks blew out on us. One

hot day we used a whisky bottle; it was made of

thinner glass than beer bottles, and the yeast blew

the entire neck off the bottle.

When we made our camp bread, we mixed the yeast into

the dough and then left it in a warm place to rise.

Then we punched it down twice. The last time it was

punched and kneaded up, then put in the camp-oven

and hung up high over the fire to rise. When it had

risen enough, sometimes lifting the lid on the

camp-oven, we hung the camp-oven low over the big

embers away from any flames. Matai was exceedingly

good for making hot embers and there was plenty of

it around the camp in those days.

We also made yeast buns with sultanas thrown in

which made them come out with an appetising smell.

And sometimes we made dumplings boiled in a kerosene

tin. They rose well and were very light and dry. And

with sultanas in them and butter put on them while

they were hot they made choice eating. There

was a bank with water trickling just below our

Aranui camp and we dug a shelf out among the ferns

to keep some of our butter and meat cool.

Billies were used for boiling the vegetables and

fruit etc. One billy was specially kept as the tea

billy. We always had a ledge of soil sods built up

or shelves split from trees to put our billies or

pots on to keep warm There was always plenty of wood

about all round the camp and our fire was never

completely cold.

When going out to work for the day we covered the

heaped glowing embers with a good depth of ashes and

embers would last two days. We only had to uncover

the embers, put on some small wood and it would burn

instantly with no delay. In the split slab chimney

we hung three pieces of chain, and made S-hooks so

as we could hang camp oven or billies etc any

distance we needed above the fire to get correct

heat.

Mangamahu >

Merv's Yarns > When

I was little - Outside

the pub

- School

years - Pioneering -

Cowboy - The

Murder - Our Bush Camp

Top - NZ

Folk home - About

Merv Addenbrooke - More

NZ murders

|