Maori Songs - Kiwi Songs - Search - Home

|

|

E p? t? hau he wini raro, He h?mai aroha Kia tangi atu au i konei; He aroha ki te iwi Ka momotu ki tawhiti ki Paerau Ko wai e kite atu? Kei whea aku hoa i mua r?, I te t?nuitanga? Ka haramai t?nei ka tauwehe, Ka raungaiti au, e. |

Your

breath touches me, o north

wind bringing sorrowful memories so that I mourn again in sorrow for my kin lost to me in the world of spirits. Where are they now? Where are those friends of former days who once lived in prosperity? The time of separation has come, Leaving me desolate. |

| E

ua e te ua e t?heke Koe i runga r?; Ko au ki raro nei riringi ai Te ua i aku kamo. Moe mai, e Wano, i Tirau, Te pae ki te whenua I te w? t?tata ki te k?inga Koua hurihia. T?nei m?tou kei runga kei te Toka ki Taup?, Ka paea ki te one ki Waihi, Ki taku matua nui, Ki te whare k?iwi ki Tongariro. E moea iho nei Hoki mai e roto ki te puia Nui, ki Tokaanu, Ki te wai tuku kiri o te iwi E aroha nei au, ?. |

O

sky, pour down rain from above, while here below, tears rain down from my eyes. O Wano, sleep on at Mt Titiraupenga overlooking the land near our village that has been overturned. Here we are beyond the cliffs of western Lake Taupo, stranded on the shore at Waihi, near my great ancestor Te Heuheu Tukino lying in his tomb on Mt Tongariro. I dream of returning to the hot springs so famous, at Tokaanu, to the healing waters of my people, for whom I weep. |

The musicI used to sing Gregorian chant in our Catholic church in the 1950s, and the above tune seems to be similar to the lamentations we sang in the last week of Lent. Perhaps that is where this was borrowed from. There is the score of different music, presumably the original chant, HERE. Background storyRore Erueti has the composer of this song as Rangiamoa of Ngati Apakura, one of the principal tribes of Waikato, although she may have borrowed the last ten lines from an earlier chant. Sir Apirana Ngata (Nga Moteatea Part I) has Rahi of Ngati Apakura as composer.

This song was popularised by Wenerata Te Heuheu,

daughter of Te Heuheu Iwikau, and she is sometimes

mistakenly attributed as the originator of this

waiata. Waikato sing this at all occasions,

although it is clearly for tangihanga. |

|

|

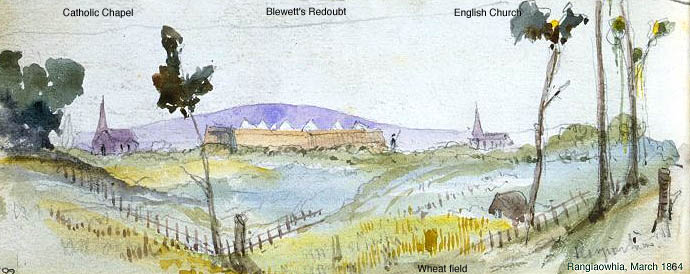

Then after the nearby Battle of Orakau two months later, Ngati Apakura were thrust out of their homes, and their lands were confiscated. A

section of Ngati Apakura then travelled south

toward Taupo. In lamenting the death of her cousin, Rangiamoa was mourning the fate of all her people. James Cowan writes....

Auckland farmers resented Maori competition because Maori were undercutting them in the market. The Maori tribes, while growing European crops and using European equipment, retained their traditional communal methods of organised work. This was the secret of their success, enabling them to produce crops at lower costs than the European farm system with profit-taking landowners and non-labouring supervisors taking 80% of the returns. So European farmers changed over to sheep and cattle farming, while Maori farmers stuck to growing crops. The growth of two different styles of farming led to numerous petty squabbles. Maori pigs rooted in European pastures and European cattle destroyed Maori crops. European merchants went in for trading arms and alcohol, and Maori people got into debt. The merchants wanted land to pay the debts. |

In

1855 the Waikato tribes produced 5,500 tons of

wheat and 600 tons of potatoes. This was valued at

£105,472.

In

1855 the Waikato tribes produced 5,500 tons of

wheat and 600 tons of potatoes. This was valued at

£105,472.