Kiwi

songs - Maori songs - Home

A bewildered British soldier in the Taranaki bush country

tries to

console a dying comrade after an ambush by Titokowaru's men.

|

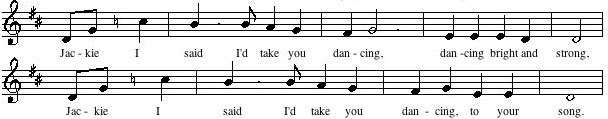

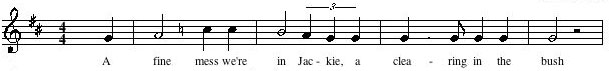

A fine mess we're in Jackie Jackie I said I'd take you dancing... |

The New Zealand WarsWith the introduction of the more easily grown potato in 1769, warfare became more intense. Tribes in Northand became especially susceptible to attack from further south by war parties in huge kauri war canoes propelled by potato-fuelled paddlers. In 1815 the Northlanders purchased muskets (and later small cannon) for retaliatory raids into the Auckland, Coromandal, Waikato and Bay of Plenty areas. Over the next 20 years, other tribes raced to arm themselves in a similar fashion before being exterminated. The gun-fighters developed tactics and structures, such as quick-firing guns, coordinated covering fire and quickly-built fortifications with gun slits, trenches and dugouts, which were copied by other armies in later wars. In about 1820 musket-armed raiders threatened the north Taranaki coast, so most of its Te Ati Awa inhabitants vacated the district and moved to the Kapiti and Picton regions. In 1860 British colonists in New Plymouth made a dubious deal to buy this mostly empty land. Te When Ati Awa leaders vetoed the sale and built a ring of gun-fighting redoubts to guard their land, the British government responded by sending soldiers from England and Australia. They needed 12,000 troops to contain the 5000 Maori, who only withdrew each time they ran out of potatoes and had to go home to grow more. Fighting in an alien landscapeJackie's Song places a pair of British soldiers just after an ambush in that campaign. This song is not about the the rights and wrongs of the colonists' actions, but about fighting so far from home in a land where nothing is familiar, where nature never lets up. The landscape is far beyond the understanding of this pair of soldiers, and their predicament highlights that of so many of the colonists, who had to confront a culture that was far beyond their understanding. The young men in England and Ireland joined the army because they had to get out of where they were; their conditions at home were atrocious, and the songs of the old men at home had told them that excitement and adventure was to be found in the army. Instead of demonizing one side or another, this song leads our imaginations into their lives so they are real people caught up in the history of their time, and now faced with death so far from home. Don McGlashin Born in 1959, singer-songwriter Don McGlashin grew up in the

midst of a music-loving Auckland family. From an early age

he loved to sing, and he played every instrument he could

get his hands on.

Born in 1959, singer-songwriter Don McGlashin grew up in the

midst of a music-loving Auckland family. From an early age

he loved to sing, and he played every instrument he could

get his hands on. After attending Auckland University he has spent all his adult years as a full-time musician, songwriter and composer. He started his career as a member of a number of bands including Blam Blam Blam and The Front Lawn in the 1980s, and then the Mutton Birds in the 1990s. He then embarked on a solo concert career, with breaks in between to score feature films and television shows. His best-known songs are Anchor Me, Dominion Road and Nature. He told an interviewer that he considered our life's work must be an attempt to understand love "...an unstable and dangerous element, but it's the fuel the world runs on." Performing this songHere, transposed into the key of D, you can see how the usual C sharp is lowered to C natural.

Although he ranges across all seven notes of the scale in the lyrical choruses of the song, Don keeps to a more restricted four-note range, mainly using the dominant fourth, to sing the expository verses,  Instead of the usual EADGBE guitar tuning, Don says he uses an EBBEBE tuning to play his accompaniment for this song. Draft

webpage put onto folksong.org.nz website Feb 2013,

modified July 2021 |