Eight books you are forbidden from reading

THE ECONOMIST, Feb 2023

Ovid was exiled by Augustus Caesar to a bleak

village on the Black Sea. His satirical guide to seduction “The

Art of Love” was banished from Roman libraries. In

1121 Peter Abelard, known for his writings on

logic and theology, and for the seduction of his student Héloïse,

was forced by the Catholic church to burn his own book

about their love for each other. And in perhaps the most

famous modern example of hostility to literature, Iran called for

the murder of Salman Rushdie, author of “The

Satanic Verses”, in 1989. For its perceived blasphemy, the novel

remains banned in at least a dozen countries from Senegal to

Singapore.

Book-banning remains a favourite tool of the autocrat and the

fundamentalist, who are both genuinely threatened by the wayward

ideas that literature can contain. In democracies books can

provoke a different sort of panic. Armies, prisons, prim parents

and progressive zealots all seek to censor literature they fear

could overthrow their values.

Bans on books that shock, mock or titillate reveal much about a

time and place. They invariably attract legions of curious

readers, too. Here are eight books you shouldn’t read.

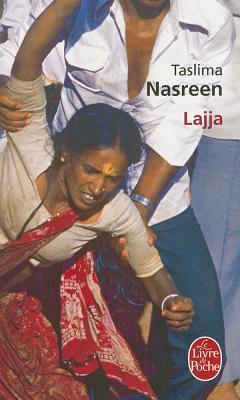

Lajja. (“Shame”) By Taslima Nasrin. Translated by

Anchita Ghatak.

Lesser-known than the fatwa condemning Sir Salman to death, but

probably inspired by it. Her novel depicts the revenge meted out

by  Muslims

to Bangladesh’s Hindu minority after a Hindu mob tore down a

mosque in Ayodhya in India in 1992. It observes the Dutta family,

who still bear the scars of earlier spasms of anti-Hindu violence;

each member of the family deals in their own way with the latest.

Muslims

to Bangladesh’s Hindu minority after a Hindu mob tore down a

mosque in Ayodhya in India in 1992. It observes the Dutta family,

who still bear the scars of earlier spasms of anti-Hindu violence;

each member of the family deals in their own way with the latest.

Bangladesh’s government

banned the book. Ms Nasrin fled to Sweden and won the European

Parliament’s Sakharov prize for freedom of thought in 1994.

Photocopies of “Lajja” spread in Bangladesh; in India, Hindu

fundamentalists distributed it as propaganda on buses and trains.

Yet her novel was less about the conflict between Hindus and

Muslims, said Ms Nasrin, than about that “between humanism and

barbarism, between those who value freedom and those who do not”.

The story still reverberates: a temple to Ram, a Hindu god, will

open in 2024 on the site of the destroyed mosque.

Friend. By Paek Nam Nyong. Translated by Immanuel Kim.

“Friend” is the first novel approved by North Korea’s totalitarian

regime to be available in English. Published in 1988, it is a

beloved classic there. A compassionate account of characters

caught up in marital strife and disappointed by their spouses, it is based on Paek Nam Nyong’s experience of sitting in on North

Korean divorce hearings.

it is based on Paek Nam Nyong’s experience of sitting in on North

Korean divorce hearings.

It is the government of the country’s democratic neighbour, South

Korea, that has banned the book for some readers. “Friend” is sold

in the South’s bookstores. But its defence ministry includes it in

a list of 23 “seditious books” banned for reading in the

South Korean army (among them are two by Noam Chomsky, a

linguist with radical politics). This prohibition applies to all

male citizens for the 18 months, or more, of their mandatory

military service.

The ministry’s apparent fear is that a sympathetic portrait of

South Korea’s hostile northern neighbour could undermine soldiers’

resolve to defend their country, and Readers of “Friend” can

expect some socialist-realist moralising. But this novel’s power

is in its depiction of ordinary lives.

The Devils’ Dance. By Hamid Ismailov. Translated by

Donald Rayfield.

When Hamid Ismailov was forced to flee Uzbekistan in 1992,  he

stood accused by his government of “unacceptable democratic

tendencies”. In exile ever since, Mr Ismailov has written more

than a dozen novels. All are banned in Uzbekistan.

Aptly, “The Devils’ Dance”—the first of his Uzbek novels to be

translated into English—reimagines the lives of real Uzbek

dissident intellectuals during their time in prison before their

executions in 1938. They include the protagonist, Abdulla Qodiriy,

a poet and playwright, and Choʻlpon, who translated Shakespeare

into Uzbek. When Qodiriy was locked up by Stalin’s secret police,

a novel he had been writing on 19th-century khans, spies and

poet-queens was destroyed. Mr Ismailov imagines that, in his cell,

Qodiry reconstructs the novel he had been writing.

he

stood accused by his government of “unacceptable democratic

tendencies”. In exile ever since, Mr Ismailov has written more

than a dozen novels. All are banned in Uzbekistan.

Aptly, “The Devils’ Dance”—the first of his Uzbek novels to be

translated into English—reimagines the lives of real Uzbek

dissident intellectuals during their time in prison before their

executions in 1938. They include the protagonist, Abdulla Qodiriy,

a poet and playwright, and Choʻlpon, who translated Shakespeare

into Uzbek. When Qodiriy was locked up by Stalin’s secret police,

a novel he had been writing on 19th-century khans, spies and

poet-queens was destroyed. Mr Ismailov imagines that, in his cell,

Qodiry reconstructs the novel he had been writing.

The Bluest Eye. By Toni Morrison.

Toni

Morrison’s celebrated novel about beauty and racial self-hatred

has long appeared on lists of books banned in some

of America’s high schools. Parents complain about

passages that depict sexual violence; teachers counter that such

topics are best broached in the classroom. “The Bluest Eye” was

the fourth-most-banned book in the school year ending in 2022,

says PEN America, a free-speech body. (Ahead of it were two on

LGBT themes and a novel about an interracial teen couple.) The

American Library Association (ALA) says that its tally of ban

requests from school boards and removals from library shelves has

never been so high: 1,600 titles in 2021. The political stakes

have grown. In 2016 Virginia’s legislature passed the “Beloved

bill”—named for another of Morrison’s controversial novels—to

allow parents to exempt their children from reading assignments if

they consider the material to be sexually explicit. The state’s

Democratic governor vetoed the bill; his opposition to it was one

reason he lost a bid for re-election to a Republican in 2021.

“There is some hysteria associated with the idea of reading that

is all out of proportion to what is in fact happening when one

reads,” Morrison said—more than 40 years ago

Toni

Morrison’s celebrated novel about beauty and racial self-hatred

has long appeared on lists of books banned in some

of America’s high schools. Parents complain about

passages that depict sexual violence; teachers counter that such

topics are best broached in the classroom. “The Bluest Eye” was

the fourth-most-banned book in the school year ending in 2022,

says PEN America, a free-speech body. (Ahead of it were two on

LGBT themes and a novel about an interracial teen couple.) The

American Library Association (ALA) says that its tally of ban

requests from school boards and removals from library shelves has

never been so high: 1,600 titles in 2021. The political stakes

have grown. In 2016 Virginia’s legislature passed the “Beloved

bill”—named for another of Morrison’s controversial novels—to

allow parents to exempt their children from reading assignments if

they consider the material to be sexually explicit. The state’s

Democratic governor vetoed the bill; his opposition to it was one

reason he lost a bid for re-election to a Republican in 2021.

“There is some hysteria associated with the idea of reading that

is all out of proportion to what is in fact happening when one

reads,” Morrison said—more than 40 years ago

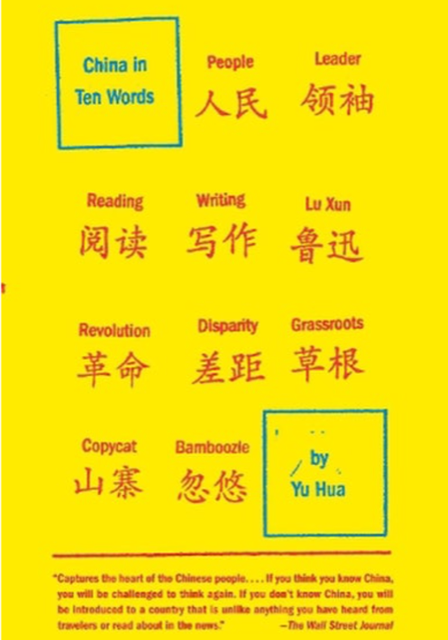

China in Ten Words. By Yu Hua. Translated by Allan H.

Barr.

China’s

government keeps tight control over printed matter: censors

scrutinise works before they go to print. But the boundaries for

fiction can be more fluid. That let Yu Hua become a best-selling

author in his native country of novels that depict China’s journey

from the brutality of the Cultural Revolution to the dislocations

wrought by materialism. But Mr Yu saw commonalities between

history and the present, and to expand on these he turned to

non-fiction. “China in Ten Words", a collection of essays each

built around a Mandarin term, is a mixture of memoir and

meditation on past and contemporary China.

It could not be published in that country. The first chapter,

“People”, refers to the bloodshed at Tiananmen Square in 1989. Mr

Yu refused to excise it. In expounding on words from “Revolution”

to “Bamboozle” he offers a view of how China got to where it is

now.

China’s

government keeps tight control over printed matter: censors

scrutinise works before they go to print. But the boundaries for

fiction can be more fluid. That let Yu Hua become a best-selling

author in his native country of novels that depict China’s journey

from the brutality of the Cultural Revolution to the dislocations

wrought by materialism. But Mr Yu saw commonalities between

history and the present, and to expand on these he turned to

non-fiction. “China in Ten Words", a collection of essays each

built around a Mandarin term, is a mixture of memoir and

meditation on past and contemporary China.

It could not be published in that country. The first chapter,

“People”, refers to the bloodshed at Tiananmen Square in 1989. Mr

Yu refused to excise it. In expounding on words from “Revolution”

to “Bamboozle” he offers a view of how China got to where it is

now.

Piccolo Uovo. By Francesca Pardi. Illustrated

by Altan.

And Tango Makes Three. By Peter Parnell and Justin

Richardson. Illustrated by Henry Cole.

What

harm could one small, anthropo-morphic egg do? A lot, if you ask

the mayor of Venice. In

2015, within days of being sworn in, Luigi Brugnaro ordered

Venetian nursery schools to ban 49 children’s books deemed a

threat to “traditional” families. Uproar ensued, and Mr Brugnaro

agreed to reinstate all but two of the books.

What

harm could one small, anthropo-morphic egg do? A lot, if you ask

the mayor of Venice. In

2015, within days of being sworn in, Luigi Brugnaro ordered

Venetian nursery schools to ban 49 children’s books deemed a

threat to “traditional” families. Uproar ensued, and Mr Brugnaro

agreed to reinstate all but two of the books.

One still off-limits is “Piccolo Uovo”, a delightful tale inspired

by the real story of a penguin egg adopted by two male penguins in

New York’s Central Park Zoo. Piccolo uovo (“Little egg”) is afraid

to hatch because it wonders what its family will look like. It

goes on a journey to meet families of many compositions and

colours, and is satisfied that all are magnificent.

Readers old and young who do not speak Italian might instead seek

out an American children’s book about the same penguins that makes

the same point: “And Tango Makes Three” has appeared on nine

occasions in the ALA’s annual list of top-ten books banned from American

libraries.

The Bible. By various authors. Translated by various

people.

Parts are deemed by some religious traditions to be the word of

God. Others bring the good news of Jesus. But the two-volume work

has its first murder in its fourth chapter. And there is no

mistaking the erotic charge of the Song of Songs. In June 2023 a

school district in Utah

removed the King James version of the Bible from the shelves of

elementary and middle-school libraries under a state law that

permits the ban of “instructional material that is pornographic or

indecent”. This petition was brought by a parent frustrated with

bans of other books, including “The Bluest Eye”.