1.

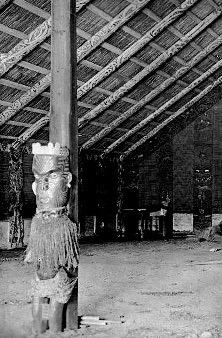

Pātaka.

A storehouse. There are two types of pātaka:-

a. Pātaka kai, for storing food, a utilitarian pantry that rats, mice and

cockroaches can't get into. Here is a pākata in Ohinemuta

in the 1850s.

for storing food, a utilitarian pantry that rats, mice and

cockroaches can't get into. Here is a pākata in Ohinemuta

in the 1850s.

I spent my WW2 preschool years with my mum and

grand-parents in the old Mangamahu hotel, built in the

days of clay tracks, when several months supply of wheat,

sugar, oatmeal and chook food was stored for winter in a

rat-proof little house on stilts and called what I thought

was the Pa Tucker, like the jolly swagman's tucker-bag. My

Grandad's Maori vocab was quite different from that of

today's Pakeha. No talk of iwi, mahi, or Fanga-ehu. He

talked of getting his pikau and pōtae before repairing the

'puckerooed' konaki he needed to haul some pungas from

near the W'ong'ehu river.

b. Pātaka whakairinga korero, a storehouse for

hanging stories. This referred to the stories in the

patterns carved in rafters and woven into wall panels of a

wharepuni, but metaphorically it can be a geographic

feature so-named to remind us of something historical,

like the Whanganui estuary that reminded the Polynesian

settlers of Fa'anui harbour back in Rangiatea. It could

also be used to describe archived documents like Apirana

Ngata's four volumes of moteatea, or a teller of

traditional stories like "old Aunty Queenie down at

the marae." Or this website!

Were there also Pataka taonga for the

safekeeping of greenstone carvings, ariki's cloaks

etc?

This waiata refers to some of the stories stored on

the mountain:

it

is a topknot giving status,

it

nourishes the island with minerals,

it

supports the heart of the people,

it

produces milky waters like whale's milk,

it

is a sleeping giant

it

provides healing waters

it is a

boundary marker

2.

Paretaitetonga

The "protective topknot of the southern

seas," is now just the topo-graphical name of Ruapehu's

most eastern peak, but it is a far more poetic name for

our mountain than "Exploding Hole."

Pare, koukou and tikitiki can all be used to describe a

topknot.

The root meaning of pare is "ward off, protect". The

lintel above the door of a wharepuni is also called a pare

because those who pass under it are moving into the domain

of Rongo, the god of peaceful activities.

The root meaning of kou is "a knob" => so koukou is a

knobby topknot, i.e. it is a bun.

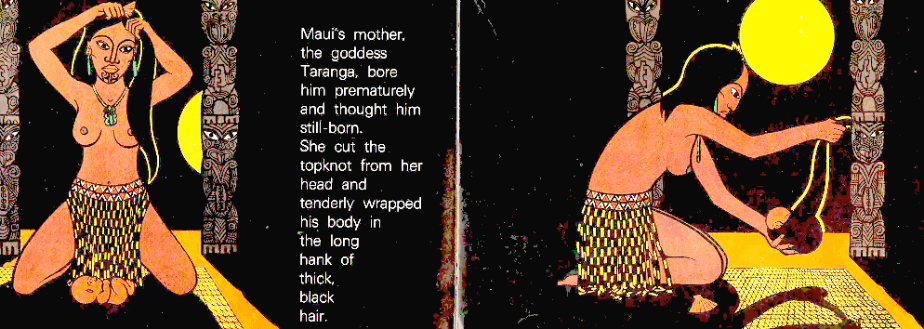

The root meaning of tikitiki is "going back and forth"

=> plaiting => so a tikitiki topknot would be

plaited. Thus Maui Tikitiki's mother plaited her hair

around him after his premature birth.

Topknots were a favourite among high

ranking-Maori. Every person's head is tapu, and a person

of higher status showed it by his specially dressed hair,

with huia feathers, combs and oils being used to create

various hairstyles.

Thus Ruapehu, decorated with its huia feather of rising

smoke, displays the mana of the mountain, as well as the

mana of the iwi who live beneath it and who protect the

mountain's mana in return.

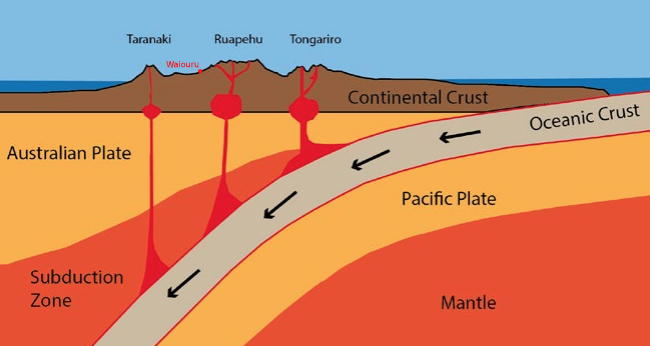

The Polynesian settlers who settled around Ruapehu were

excellent agriculturalists, and they recognized that the

periodic deposits of ash from the "topknot" provided the

minerals and soil texture helping to maintain the fertility

of the land. Even today, the root vegetables grown beneath

the mountain give this region a special status.

Paretaitetonga is first mentioned in print in the

New

Zealander, May 1851, as a poetic refuge for the

survivors of the 1822 Matakitaki massacre.

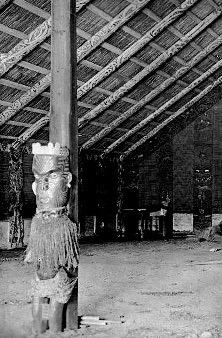

3. Pou-toko-manawa

This is the post in the centre of a wharepuni

meeting-house that keeps its ridgepole from buckling. But

all Polynesian languages, including Te Reo Māori, are

poetic, with layers of meaning: the wharepuni building

represents the iwi's founder, and Pou-toko-manawa means "the

pole supporting the heart of

our founder."

Nearly all of us have someone who has given us support and

space to move when the weight of the world was pressing

down on us; mother, teacher, big sister, workmate.... (who

was yours?) and Mt Ruapehu is a pole supporting us by

giving us unique status and sheltering us from cyclonic

winds. It provides us with fertile volcanic ash for our

vegetable industry, with sharp winter weather to keep

those veges chilled until wanted, a plentiful supply of

fresh water, a tourist industry --- and millennial

protection from Taupo's nuclear-force eruptions!

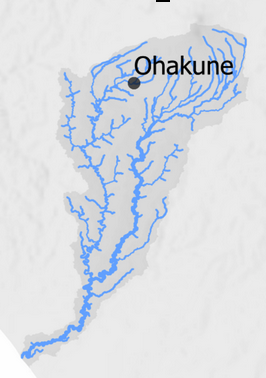

4. Te

Waiū-o-te-Ika

"The Milk of Maui's

Fish" is the Whangaehu/Mangawhero water catchment.

Children

are told that 'Maui used his grandfather's jawbone to

pull up a giant fish.'

Children

are told that 'Maui used his grandfather's jawbone to

pull up a giant fish.'

This summarizes how Kupe was motivated with an

adventurous 'Maui' spirit that implanted in him from years

of having his adventurous grandfather Maru-tawiti

jawboning on about how he could get through those cold

rough seas far to the south to get up in the high

latitudes where 100,000 whales and untold millions of

seabirds migrated to every year: "There must be

some huuuge motu up there, eh boy? But you'll

need really strong high bowposts and sternposts to be

your four taniwha to part the huge killer waves, you

must take wind-and-waterproof korowai to fight the ice

demons, and you must remember to leave Rarotonga in

December when the prevailing sou-westerly headwinds

change to nor-easterly tailwinds; OK boy?"

Eventually,

as those nor-easterlies made world rotate under his

vessel, Kupe and his crew spotted great long clouds of

white fish-catching birds, millions of them. Then the

mother of all whales, Te-Ika-o-Maui, came up over the

horizon spouting volcanic 'water vapour' as she appeared.

Whales give milk, and both the Whangaehu and Mangawhero

rivers have milky-coloured headwaters (volcanic ash and

precipitated silica respectively).

Eventually,

as those nor-easterlies made world rotate under his

vessel, Kupe and his crew spotted great long clouds of

white fish-catching birds, millions of them. Then the

mother of all whales, Te-Ika-o-Maui, came up over the

horizon spouting volcanic 'water vapour' as she appeared.

Whales give milk, and both the Whangaehu and Mangawhero

rivers have milky-coloured headwaters (volcanic ash and

precipitated silica respectively).

In 2018, the Government of New Zealand and the Ngāti Rangi

iwi signed a deed of settlement providing for, among other

things, a redress framework for the Whangaehu River, known

as the Te Waiū-o-te-Ika Framework, with Te

Waiū-o-te-Ika meaning the living and indivisible

whole of the Whangaehu River and its tributaries, its

physical elements (including minerals) and metaphysical

elements, from Te Wai ā-Moe crater lake to the sea.

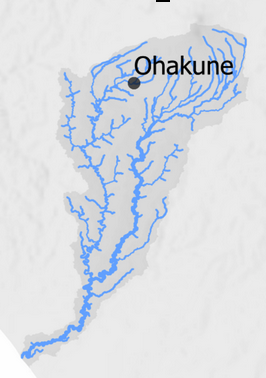

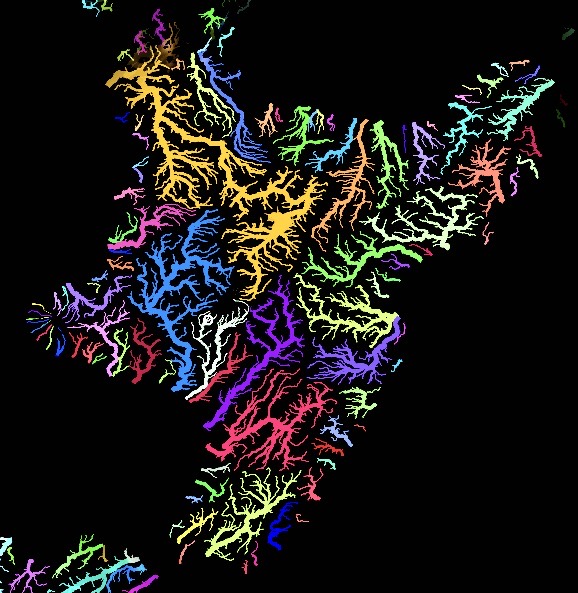

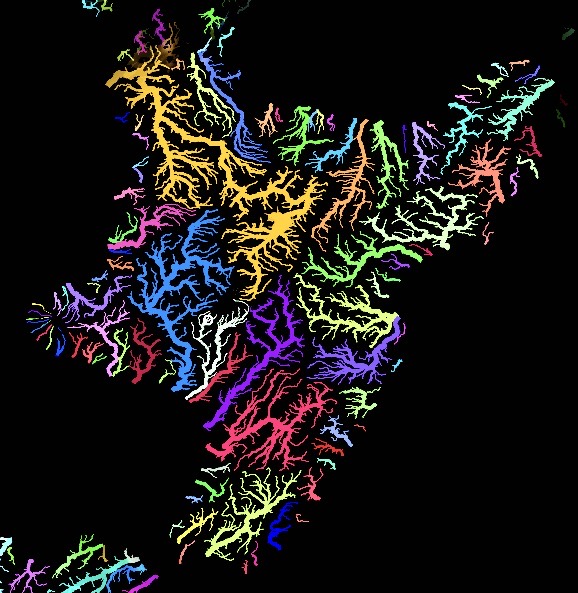

Te Waiū-o-te-Ika

O =

Ohakune. How many other rivers and streams can you

name?

5. Te Wai Ā-moe

There was very little activity in Ruapehu’s crater lake

in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The volcano seemed to

be sleeping, and consequently the lake became a tourist

attraction. The lake was filled by melting snow and summer

rain, and these waters were heated by steam rising from

the lake bed.

Renewed volcanic activity after 1965 made the lake more

acidic and more unpredictable, resulting in small

steam-blast

eruptions in 1980, sending a high-density mix of very

hot lava blocks, pumice, ash and volcanic gas across the

lake's surface.

Then in 1995-96 it erupted massively and repeatedly.  <

<

6. Wai-ariki

Ariki were chiefs, leaders, those of high rank, and in

districts where the were no geothermal pools, wai-ariki

were baths prepared to ease the aches and pains of elderly

ariki by heating rocks in a fire, then dropping the rocks

into a small pool to heat the water. Titoki berries may

have been added to scent the water, and kumarahou leaves

to make it soapy.

(Can anyone give me more

information about these therapeutic baths?)

But the hot water in Ruapehu's crater lake, and in the

more accessible Ketetahi hot springs 800m lower down the

mountain, provided chiefly hot baths for everyone in the

iwi !

As well as some pleasantly warm waiariki in Ketetahi

Springs, there are dozens of mudpools, boiling springs,

and exploding steam fumaroles over an area of about 30

hectares, with an energy output of about 100 megawatts, so

beware!

Ngatoro-i-Rangi

The tohunga/navigator of the Arawa voyaging walked south

to the central North Island six centuries ago, re-naming

land and then claiming it as he went, and in the course of

his travels he ascended the mountains' central lofty cone

in order to survey the surrounding country. He was

caught at its summit in a snowstorm, and he used these

words in his prayer to his goddess 'sisters' who now

resided on the very explosive Whaka-ari that we call White

Island.

"E Kuiwai e! E Haungaroa e! Kua riro au i te tonga;

Haria mai he ahi moku!"

"0 Kuiwai, 0 Haungaroa! I

am being borne away by the south

wind.

Send some fires for me!"

From the words "riro" (borne away, seized) and "tonga"

(south, wind) used in the land-hunter's cry came the name

Tonga-riro.

As for the name Ngauruhoe, he had a slave girl

named Uruhoe with him as a guide and porter, one of the Te

Tini o Toi people who had arrived in an earlier migration,

and he slew her on the mountain top as an offering to his

goddess sisters, in order to give additional force to his

prayer for fire. When fire did come from the crater, he

threw her body into the inferno as thanks.

It would appear that his goddess sisters threw three

'baskets' of fire to him, with one basket falling short at

the aptly named Kete-tahi, one going too far, to Ruapehu,

and the last one hitting the sweet spot.

My question is where did the plural 'Nga' come from in

front of Uruhoe?

I think the original lass had a rather explosive

temperament, and a fiery spirit that would have become

more and more fiery and explosive when they were trapped

on the summit.

"I told you, I told you there was a storm

coming; I told you!"

I korero ahau ki a koe kei te haere mai he tupuhi ; I

korero ahau!

My guess is he killed her in the hope that all this fiery

spirit would pass on to the mountain. And also to stop her

yelling at him.

So was the volcano's original name Nga-ahi-o-Uruhoe: The

fires of Uruhoe?

7.

Whangaehu

Whanga-ehu = an estuary that is murky. A children's fable,

He Potiki Mo

Wharaurangi, tells them that this river, and others

up and down the same coast, were given their descriptive

names by Hau, an ariki who came on the

Aotea

voyaging waka and whose wife had run off with one of

the

Multitudes of Tio, descendants of the island's first

settlers.

Children were helped to remember the Whangaehu river's

name and location by being told that its muddy bottom

was stirred up,

tiehutia,

as Hau ran through it in pursuit of his

wife's seducer.

Of course the river, and all the other rivers listed in

this fable, would have been given their names a century

earlier by the

Multitudes of Tio. This fable served as a geography

lesson, as a warning to young wives not to go running

off with handsome strangers, and as claim to ownership

by Hau's descendants, and not by Te Tini o Tio, who

were now slaves. Name-giving implies ownership.

8.

He Pou e Poua ki Runga

"A boundary marker raised up high."

The third verse is a variation of an old karakia that is

still widely used to this day.

Poua

ki runga,

Poua ki raro

Poua ki tāmoremore nui nō Rangi

ki

tāmoremore nui nō Papa

He rongo, he āio,

Tēnā tawhito pou ka tū

E tū nei te pou!

|

Established

to great heights

Established

to great depths

Established

as a huge clear expanse

as a huge clear physical expanse

peaceful, calm

This ancient landmark is standing

and

the landmark will keep standing here.|

|

Matua Che has changed this to....

He pou, te pou i poua

ki runga

ki Rangi-tāmore-nui

He pou te pou i poua ki raro

ki Papa-tāmore-nui

Poua ki te whenua, poua ki te rangi e

|

A boundary marker, the landmark

raised up

as a big

pinnacle

leading to the spirit worlū.

the

boundary marker placed in the

island's

centre

as a

big pinnacle on

the land

Planted on the ground, leading

towards

the spirit world

|

Ruapehu's peak is the highest of many tribal boundary

markers on the volcanic plateau. I have described these

overlapping

boundary

markers in detail in my

History

of Waiouru.

It is also a boundary marker linking the spiritual and

physical worlds.

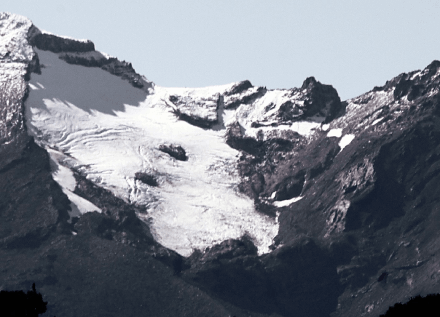

9. Hei wai

ora e, poua ki Ruapehu

The living waters are stored up on the mountain as ice in

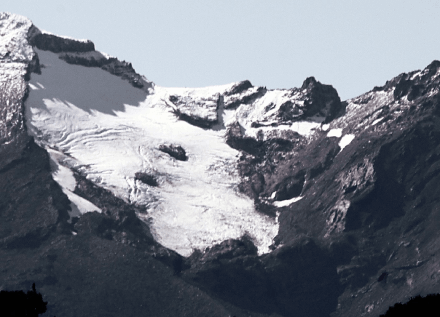

glaciers, or huka-papa, "snow-that's-solid." In winter,

fallen snow becomes compacted as ice at the top of a

glacier, and in times of summer drought, the ice at the

warmer bottom end melts and supplies water for drinking

and irrigating crops.

Mangaehuehu glacier once extended down to about 1500m

altitude, and was used to keep the birds that were

harvested in autumn 'deep frozen' to supply food for

winter.

But by the 1940s it had retreated to about 2000m and then

to 2100m by the 1970s. By 2010 it was above the rock wall

at 2250m, and was growing thinner.

Ruapehu is now hanging out a message of warning that we

have burnt too many trees, driven too many vehicles too

far, flown on too many tourist flights, generated too much

coal-fired power, farmed too many cattle beasts and dairy

cows, made too much cement, and consequently we are now

losing our supplies of life-saving stored water.

1940s

1972

2010

A Spiritual Connection

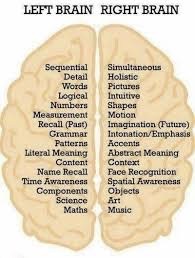

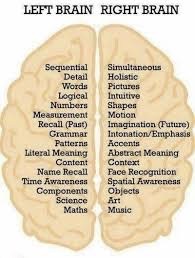

I've

had a typical Pakeha upbringing, and as Westerners, we

Pakeha were educated to think only with the conscious

fraction of our minds, or with our "left-brains," so

generally we only think in a logical, factual,

individualistic way.

To enable the soulless leaders of the British Empire to

grow rich by killing other peoples and then

asset-stripping their lands, we Pakeha have been

programmed to ignore our intuitive connections associated

with places, objects and past generations, symbolic

associations that are generated by our collective

unconscious, in our "right-brains."

But the connections are there. This is why those who have

a holistic

left-and-right brain upbringing are able to experience Ruapehu,

Te Wai Āmoe,Te Waiū-o-te-ik

a,

Rangi-tāmore-nui etc as living beings

that care for local humans and who the local humans (a

group united as one by their relationship with the great

mountain) must in turn take care of.

Endnotes

1.

In 2005, my niece, Ruth Basher, spent a year in the

Ketetahi hut working on

her

Master's thesis, which was

downgraded to 2nd-class honours because she 'wrongly'

predicted that further eruptions were likely from the Te

Maari crater, not far from the Ketetahi Springs. In

2012, hikers doing the Tongariro Crossing ran for their

lives when Te Maari did indeed erupt suddenly, as caught

in this video

sequence. Perhaps Ruth was more tuned in to her

unconscious mind than most MSc students.

2.

I spent my childhood in Mangamahu, and when I was 12,

Ruapehu sent extra wai-u down Te Awa o Whangaehu on

Christmas morning;

wai-u that brought us many 'presents.'

2.

I spent my childhood in Mangamahu, and when I was 12,

Ruapehu sent extra wai-u down Te Awa o Whangaehu on

Christmas morning;

wai-u that brought us many 'presents.'

Presents,

alas, which had to be stored in the shed

beside our house every day for several weeks, making the

river wai-kūkua for many in our village. Pillows

of the Dead.

for storing food, a utilitarian pantry that rats, mice and

cockroaches can't get into. Here is a pākata in Ohinemuta

in the 1850s.

for storing food, a utilitarian pantry that rats, mice and

cockroaches can't get into. Here is a pākata in Ohinemuta

in the 1850s.

Children

are told that 'Maui used his grandfather's jawbone to

pull up a giant fish.'

Children

are told that 'Maui used his grandfather's jawbone to

pull up a giant fish.'  Eventually,

as those nor-easterlies made world rotate under his

vessel, Kupe and his crew spotted great long clouds of

white fish-catching birds, millions of them. Then the

mother of all whales, Te-Ika-o-Maui, came up over the

horizon spouting volcanic 'water vapour' as she appeared.

Whales give milk, and both the Whangaehu and Mangawhero

rivers have milky-coloured headwaters (volcanic ash and

precipitated silica respectively).

Eventually,

as those nor-easterlies made world rotate under his

vessel, Kupe and his crew spotted great long clouds of

white fish-catching birds, millions of them. Then the

mother of all whales, Te-Ika-o-Maui, came up over the

horizon spouting volcanic 'water vapour' as she appeared.

Whales give milk, and both the Whangaehu and Mangawhero

rivers have milky-coloured headwaters (volcanic ash and

precipitated silica respectively).

<

<

I've

had a typical Pakeha upbringing, and as Westerners, we

Pakeha were educated to think only with the conscious

fraction of our minds, or with our "left-brains," so

generally we only think in a logical, factual,

individualistic way.

I've

had a typical Pakeha upbringing, and as Westerners, we

Pakeha were educated to think only with the conscious

fraction of our minds, or with our "left-brains," so

generally we only think in a logical, factual,

individualistic way. 2.

I spent my childhood in Mangamahu, and when I was 12,

Ruapehu sent extra wai-u down Te Awa o Whangaehu on

Christmas morning

2.

I spent my childhood in Mangamahu, and when I was 12,

Ruapehu sent extra wai-u down Te Awa o Whangaehu on

Christmas morning