The Murimotu Wool Wars13. Sheep on the Murimotu plains1855,

the missionary Tom Grace brings a few merino

sheep to Pukawa, just west of Turangi to

introduce local Maori to sheep-farming. The

sheep become sick on the short tussock growing

on the Taupo ash soils lacking the trace

element cobalt,

but they improve when moved to graze the red

tussock on the Ruapehu ash soils of the

Murimotu Plains. 1871, the government seeks to lease the greater Murimotu plains around Rangipo, Karioi and Waiouru. The boundaries had already been sorted out back in 1850 at a huge hui at Hihitahi chaired by Wanganui missionary Richard Taylor, but no money was at stake back then, and in the intervening 20 years the Hauhau, Titokowaru and Te Kooti wars have been fought, creating new power groups and reviving old enmities, so numerous conflicting claims are put forward.

Jan 1874, the government makes arrangements with Te Keepa, or Major Kemp, on behalf of Ngati Rangi on the lower Whanganui river, to lease 140,000 hectares of the Murimotu plains. This is to include many native reserves. Kemp hopes that a bi-cultural farming community will develop here, with many small farms. Kemp was born Te Rangi Hiwinui near Opiki in about 1825, and when Te Rauparaha’s Ngati Toa attacked the Manawatu, his mother had fled with him to Putiki Pa at the mouth of Whanganui River. From the CMS missionaries at Putiki he had learnt the advantages of a multiracial society, and, in the 1860s he became a pro-government military leader against the Hauhau, and later against Titokawaru and Te Kooti. But

Topia Turoa is one of the Hauhau leaders Major

Kemp had defeated ten years previously at the

battle of Moutua Island, near Pipiriki. He is

chief of the Tuwharetoa land between

Taumarunui and the southern end of Lake Taupo,

and he strongly contests Kemp for control of

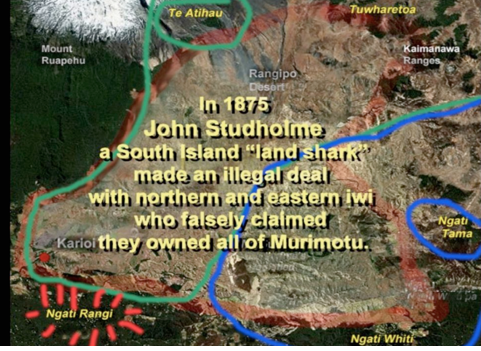

the Murimotu plains. 14. John Studholme, land sharkWhile Maori ownership of the various parts of the Murimotu was still being settled at the Wanganui Land Court, John Studholme, described by Wanganui Herald editor John Ballance as a “Canterbury land shark,” joins with Auckland lawyers to make a highly illegal deal to lease the land from Topia Turoa, and from Ngati Whiti at Moawhango. March

1874, Studholme immediately makes Karioi

his centre of operations. He moves sheep onto

the land, and starts building houses, stables

and sheds. There is a huge uproar, both from

Ngati Rangi Maori on the lower Whanganui River

who also has claims in the area, and from

other would-be wool-growers. By law, only the

government can lease Maori land. But

Studholme’s money is able to buy a lot

influence in parliament, so the government

obligingly leases the land from Topia and the

Ngati Whiti, then sub-lets it all back to

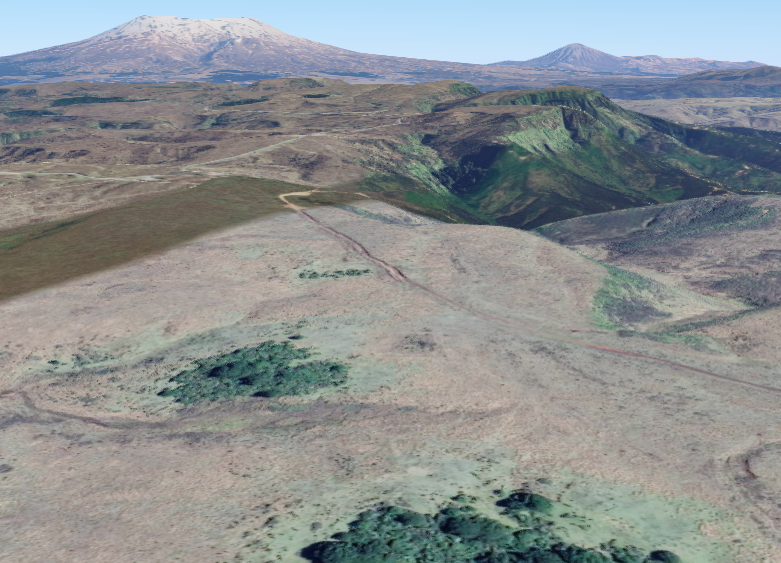

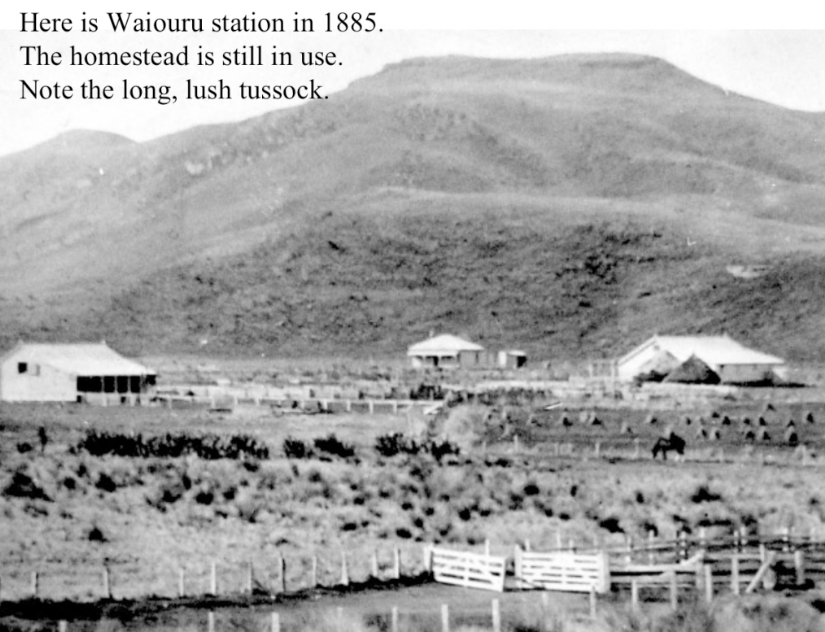

Studholme’s group. 15. Showdown at Waiu PaJanuary 1880, Studholme’s land ring tries to obtain permanent ownership of the land. This incenses the Whanganui faction and they call on Major Kemp for assistance. He re-activates his now-aging company of seasoned gun-fighters who had routed Topia at Moutua 16 years previously and they ride up out of the Whanganui valley to Waiouru.February 1880, Kemp takes command of the strategic high ground on Auahitotara at the top of Home Valley and overlooking the Moawhango Valley. His men dig rifle pits and begin some serious "live-firing exercises." This upsets the Ngati Whiti people 15 km southeast at Moawhango village, who consequently re-activate their own militia as well. These move forward to two old shepherds' lodges on the ridge 3 km east of Kemp and dig gun-fighting trenches all round them. The closest "Waiu Pa" gunpits can still be seen today.

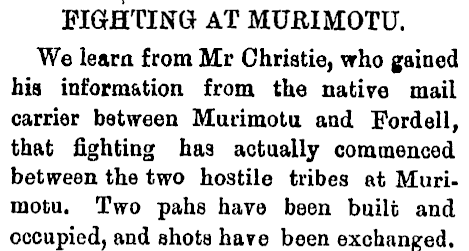

Despite the scary headlines in February 1880, the "Fighting at Murimotu" was only shooting practice. Major Kemp eases the tension with the Ngati Whiti by visiting them and explaining his dispute was not with them but with Topia Turoa, and with the Studholme land ring. The Maori missionary Herekau acts as a negotiator between Kemp and Topia, and it is agreed to settle the matter before the Maori Land Court in 12 month’s time. 1881, Turoa arranges to have the Land Court sitting at his former Hauhau village on the southern shore of Lake Taupo, where Kemp and the Ngati Rangi (who had killed so many Hauhau) are most unwelcome. Naturally the court there rules in Topia’s favour. 1883, Kemp and the Ngati Rangi bring a civil action against Studholme and his ring, seeking £3200 for the ring’s occupation and pasturing of the Rangipo-Waiu block. The High Court decides on a technical point that the defendants did not have to pay. 16. Studholme's decline1884, Studholme’s win in court is a hollow victory, because his run of luck is starting to change. Disgruntled Ngati Rangi blockade his wool sheds for the next two years, preventing several hundred tons of wool from being packed out to Napier for export and sale. With no cashflow, the land ring falls apart. Morrin and Russell go bankrupt and Moorehouse withdraws. Studholme becomes the sole lessee and by now wool prices have fallen drastically because big sheep stations in Australia have begun to export thousands of tonnes of wool. 1888, the number of sheep on Murimotu have dropped from 60,000 to 40,000 because rabbits are becoming a problem, eating much of the grass needed for Studholme’s sheep. Itinerant shearers had brought a few of them into the district to provide themselves with a change of diet from fatty mutton, and now the rabbits have multiplied to vast numbers. But costs remain high. Studholme has to pay £25 a ton to have his wool transported by packhorse to Napier, and £25 to have it shipped to England. He also has to pay an annual rent of £25 for every 1000 hectares he leases. The climate is becoming colder too. Snow had fallen on Christmas Day in 1884, and in winter the Murimotu plains are now often under snow. The winter of 1897 is a killer. A storm in May leaves snow one foot deep around Waiouru, and another storm in June brings drifts 6 feet deep, Desperate sheep move in amongst the trees to find food and shelter as snow continues to fall for the next three months. A visitor to Studholme’s farm at the end of the year finds dozens of sheep skeletons “8 to 10 feet from the ground at Circular Bush.” The deep snow has killed 20,000 Murimotu sheep, and the survivors are walking skeletons, unable to produce lambs or wool for shearing. Studholme has income from eight large properties in the South Island and five more across the North Island, but the financial losses at Murimotu have drained away his profits. He returns to England and dies there in 1903. TIME TRAVELER ACTIVITY Take a walk along the saddle track behind the Officers Mess. It starts behind the tin sheds on the old hospital lawn. Go off the track and walk in the long tussock. Notice that it slows your walking, but that the thick overhanging tussock can provide shelter for sheep, and winter feed, and that the fallen tussock seeds provide food for ground-feeding birds, like quail. Next 17. Peters' coach services |