By a Traveller

I found myself, a few weeks ago, debating where

and how I should spend a fortnight's vacation. "To Rotorua

and Auckland, via the Main Trunk, returning by the Wanganui

River," suggested itself as a profitable way in which to

spend a fortnight. That suggestion I adopted, and in due time

found myself travelling on the New Zealand railways.

A night was spent very pleasantly at Taihape, and a start made

next morning for Taumarunui. We changed into a Public Works

Department train, and then really began the Main Trunk journey.

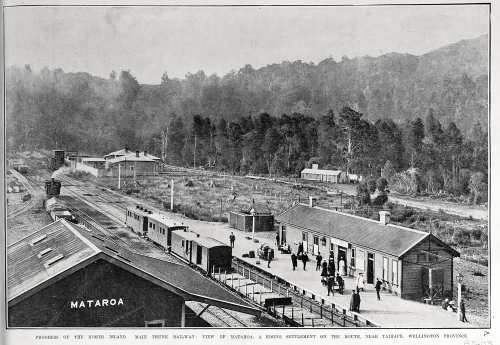

Mataroa is on the boundary of the King Country, and of course

beyond that point liquor must not be taken. The officials at the

railway station are evidently very zealous in their efforts to

prevent liquor entering the King Country.

On the morning I am writing about, not only did they carefully

examine the luggage of all the passengers, but they stopped a

drunken man from continuing his journey. By the bye, I did not

see another man under the influence of liquor until Te Awamutu

(on the other boundary of the King Country) was reached.

Beyond Mataroa some pretty bush is passed, but on reaching the

Karioi plains there are simply miles and miles of bleak,

desolate tussock land. Deserted camps, where cooperative

labourers had flourished for a time and then moved on, mark the

progress of the construction of the line.

As the railhead is reached, the traveller, who may have become

somewhat wearied by the monotonous sameness of the journey,

wakes up to the fact that he has not travelled in vain, for

scene after scene of beauty comes into view. As the train

proceeds, the bush, in all its virgin beauty, gradually closes

in upon the railway track, until the train is practically

picking its way through huge trees and magnificent ferns,

pungas, and undergrowth.

At last steam is cut off and the train draws up at the

northernmost station on the line. What a sight it is! Nothing

like it can be seen in any other part of the Dominion. It is one

never to be forgotten, but alas, in a few months the opportunity

of witnessing it will have passed away.

In the middle of the line and just in front of the engine stands

a huge tree, which, immovable and impassive, seems to say with

an imperial air—" Thus far and no farther.'' The engine

bows its head but as it thinks of the hand that has harnessed

its fount of power it merely murmers. "Thus far and no

farther —just now.' Almost up to the right hand side of

the carriages are the toweling trees of the forest, while the

shrubbery and undergrowth are standing in their primeval glory.

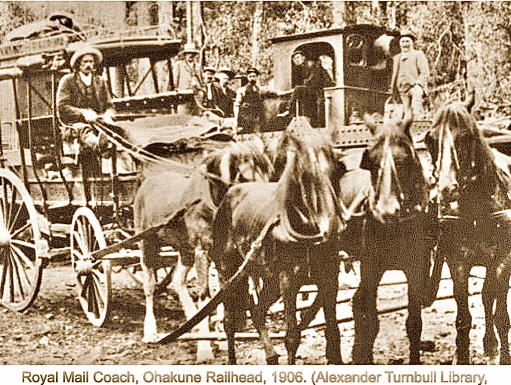

In a small clearing outside the station is a scene of

excitement. Five coaches, each with its four-in-hand, are drawn

up waiting for the passengers who have come by tho train. Great

is tho hurrying and scurrying! Seats have been booked—an agent

has seen to that at Taihape—but each person is anxious to

I know ''Which is my coach? " Then there is an excited

confab as to whether box seats have been reserved, and so forth.

In the meantime luggage has been transferred from the guard's

van to the coach boot, and a hurried rush is made to a room on

the station platform, where a placard announces afternoon tea.

Though it is very little after midday, tea proves very

acceptable, and the travellers, refreshed and contented, clamber

into their respective conveyances. Pride of place is given to

the coach which carries His Majesty's mail and in a few minutes

five whips are cracking, twenty horses are straining at

their collars, and a twenty drive of the most unique nature is

begun.

What a new world is opened up! I shall not try to describe the

beauties which Nature has strewn lavishly before the eyes of the

traveller. But I must confess to a feeling of sadness as I gaze

upon the thousands and thousands of acres of glory penned up as

it were in the slaughtering yards. Soon will the butchers go

into those pens and an acre here and an acre there, the giants

will fall and their vestments disappear in smoke.

As the coach reaches the highest point of the road one looks

down upon a vast extent of forest, the appearance of which

resembles nothing so much as an ocean in the moonlight. The

ground is evidently hill and dale, and the tops of the trees

rise and fall as it were in billows. Clouds pass across tho sun,

and the shadows skim the tree tops in a weirdly fantastical way.

But it not the scenery—a kind that is almost indescribably

grand—which makes the drive memorable. It is the opportunity

given to see the last of the co-ops—a phase of life which is

rapidly drawing to a close.

After leaving the railhead the traveller comes upon an entirely

new world with a people peculiarly its own. He finds himself in

the midst of tent land, where the pioneers of civilisation are

roughing it in order that others may travel in comfort and maybe

live in plenty on the land which is now wild and untouched. As

the coach bowls along tho excellent road which winds its way

through the bush, glimpses of towns in embryo are obtained. What

are their destinies? Perhaps we would not smile at them if we

only knew.

Here is a township the name of which we do not hear. The main

street is the coach road. On it are several small huts, to go

into which would necessitate stooping by men less stalwart than

Sir Percy Blakeney. One is the leading hotel —temperance of

course, for is the town not in the King Country? It, or at any

rate, one like it, is the Harp of Erin, and the proprietor beams

upon the coach loads as they go hurrying by. "Hop beer sold

here" does not tempt the travellers, and consequently

mine host does not add to his day's takings.

By the way, hop beer must thrive wonderfully in this no-license

district! No matter where one looks, "Hop beer sold here"

is a sign shown prominently on tents and hut walls. Tho sign

writers on the Main Trunk perhaps would not satisfy an

up-to-date art master, but they certainly achieve what an artist

might not—their signs catch the eyes of the public, and that,

after all, is the chief end of such art. The cynic may be

inclined to smile as he passes these hop beer advertisements,

and think of words often used by the professional, conjuror—but

there, the beauty and quaintness of the surroundings banish

cynicism.

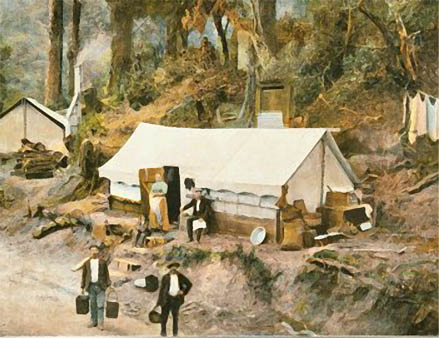

Alongside the hotel, which is also a store, is the township's

general provider, who has a wonderful assortment in his little

crib. Quaint indeed are these little pocket editions of business

houses. Then there is the residential portion. Here are the

tents where the workmen live. Each tent is supplied by the

Public Works Department, and bears the brand of the Broad Arrow.

Usually this brand is looked at askance, but on the Main Trunk

it is quite the thing. The tents are small, but some of the

inhabitants have endeavoured to secure a little comfort. Their

efforts have been in the direction of erecting tin chimneys, and

so making cooking operations more easy and pleasant than would

otherwise be the case.

No town, be it ever so small, is complete without a

boarding-bouse, and, as the coaches pass along the road, quite a

number of tents are seen bearing the sign "Boarders taken

in," with one establishment announcing board and lodging

at 17s 6d a week. "I wonder where they can put even one

boarder?" queries the traveller, but before an answer can

be given he is whirled halfway to the next township.

Practically tho whole of the population consists of men, but the

traveller now and again comes upon evidences those brave-hearted

women who have not flinched from following their husbands into

he wilds of the island. As the coach sweeps along, a glimpse is

caught of a clothes line laden with the week's wash, and through

an open door of the tent or whare is seen the white tablecloth

on which a meal is tastefully laid. Peeping through the door is

a toddler or a mother rocking her little one. Just a glimpse,

but it is a touch of Nature. Hew dreary in comparison look the

other tents!

So the coach speeds on. As Horopito is reached, rain falls in

torrents. The coach from the Waimarino end meets ours. Like us,

the passengers are hidden beneath umbrellas and wraps, and a

very merry party they seem, their laughter ringing in the air.

Horopito on a rainy day! The saints preserve us from tent

residence there!

Now we see the Main Trunk workers in a different light. All work

has been stopped, and the men have come into the "townships."

Some are standing in the lee of their tents, sheltering from the

rain, and others are congregated in their tents playing cards.

An hour passes by, during which time innumerable camps are

passed.

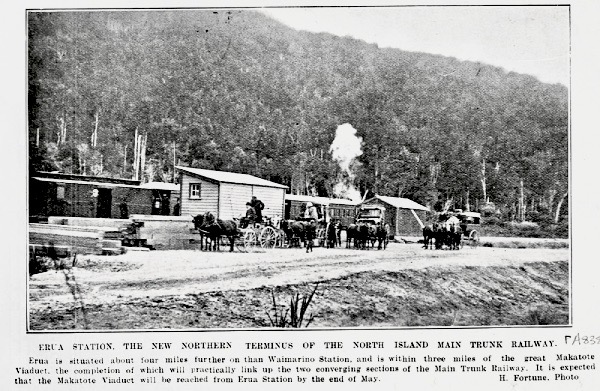

Then, as we leave the forest, the rain clears away, and almost

at the same moment we emerge on the Waimarino plains. We drive

on, and in the distance see our goal, the Waimarino station,

standing out prominently in the middle of a huge natural

amphitheatre. En route to it we pass gangs of platelayers busily

engaged laying the rails to the Erua Station, the next railhead,

which will be reached in the course of a few weeks.

At 4.40 pm our coaches swing alongside the Waimarino Station,

where a train is in waiting. So ends a drive which will always

remain a pleasant memory.

From Waimairino we dash downhill at a great speed through

magnificent bush scenery; In places the line is a triumph of

engineering skill. Especially is this the case in regard to the

Raurimu spiral, the wondrousness of which has become a household

word.

Leaving Raurimu, and still passing through glorious bush, the

train speeds on past Oio and Owhango, and a couple of miles

furtherl the Wanganud River is seen. Then follows a delightful

journey. Day is drawing to a close, and as Kakahi and Piriaka

are passed, the spirit of peace and repose seems to have

descended on the beautiful valley.

Night has now folded the land in its soft embrace, and as we

leave the train at Taumarunui, lamps have to be brought into

use. Dinner at Meredith House is is followed by a saunter

through the main street of the go-ahead town, and then slumber

ends an enjoyable day.

Source

Wanganui

Chronicle, 31st March, 1908.

Next

19.

The Rabbit Years