21. Three Hundred Tons of Nails

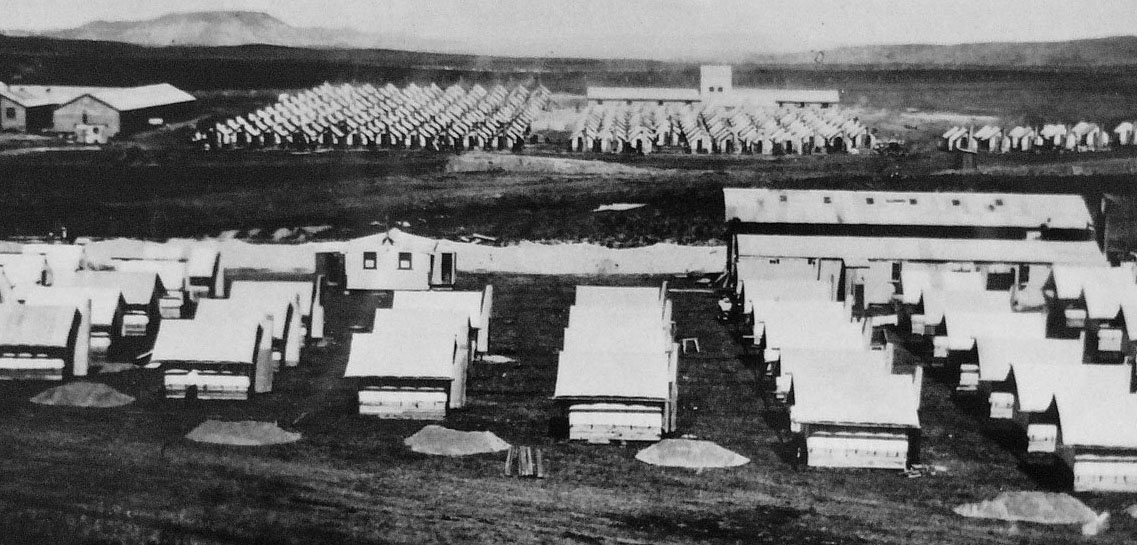

1200 tradesmen built Waiouru Army Camp in only 11

months.

October

1939

War has been declared. The government purchases

Waiouru sheep station for territorial defence. It wants a

central military base strategically sited out of range of

enemy ships but with quick road or rail access to all of

the North Island’s harbours and coastlines.

December

1939

The

Public

Works Department is ordered to build barracks at

Waiouru to house two battalions for territorial

defence. On the 2nd of June 1940 this order is

increased to buildings for training seven

battalions of expeditionary

forces.

200

Public

Works Dept engineers arrive at Waiouru. They survey

the swampy site with the Waiouru Stream flowing

through the middle of it, then begin removing the

swamp with land-scrapers and replacing it with sand

and gravel.

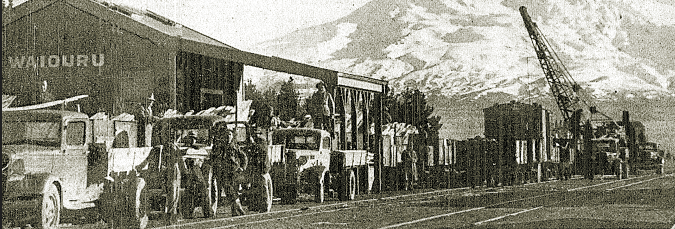

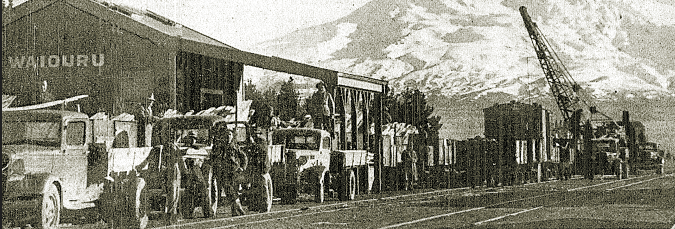

Each

day they bring hundreds of tons of building

materials to the site from the Waiouru railway

station, unloading everything by hand.

1st

July 1940

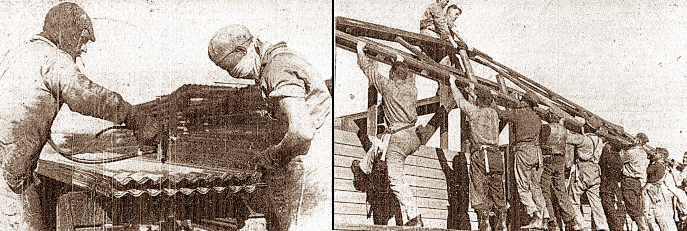

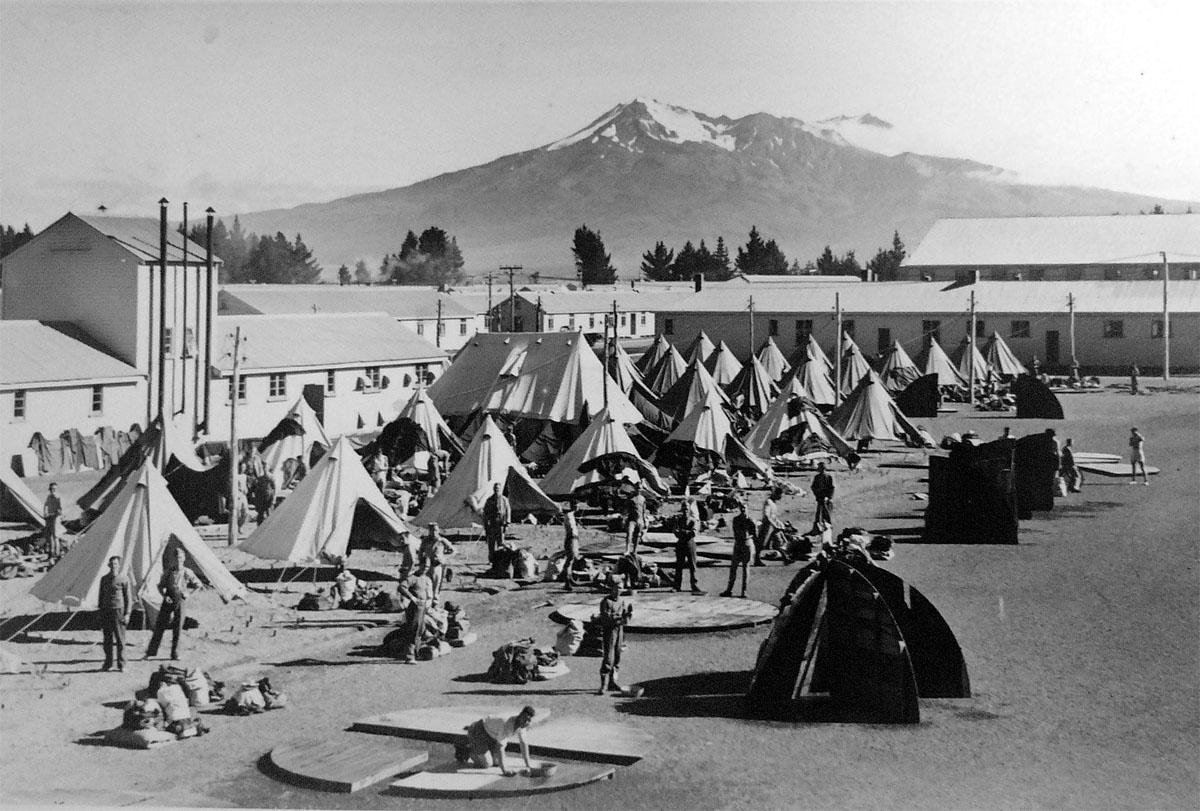

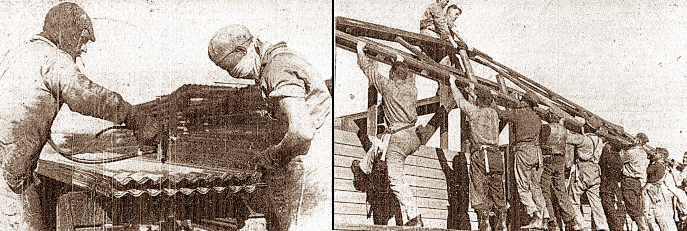

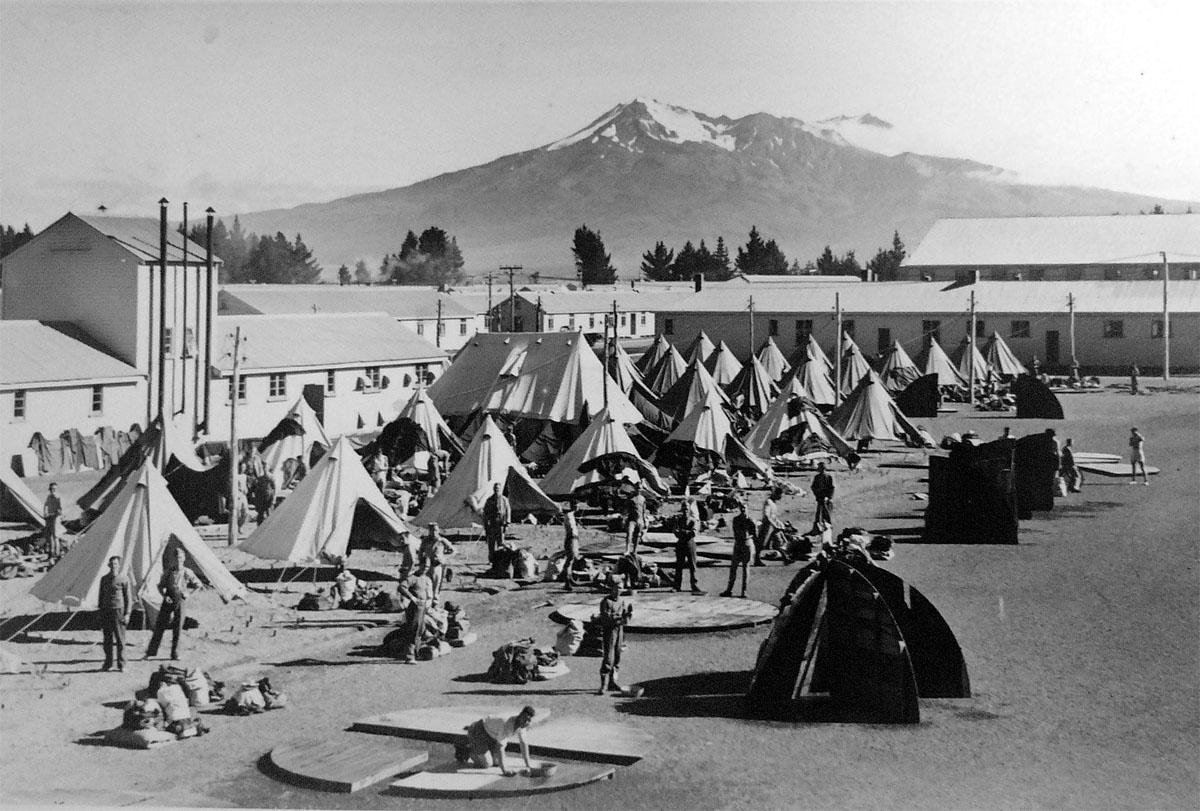

Another 800 men working for private building

contractors begin

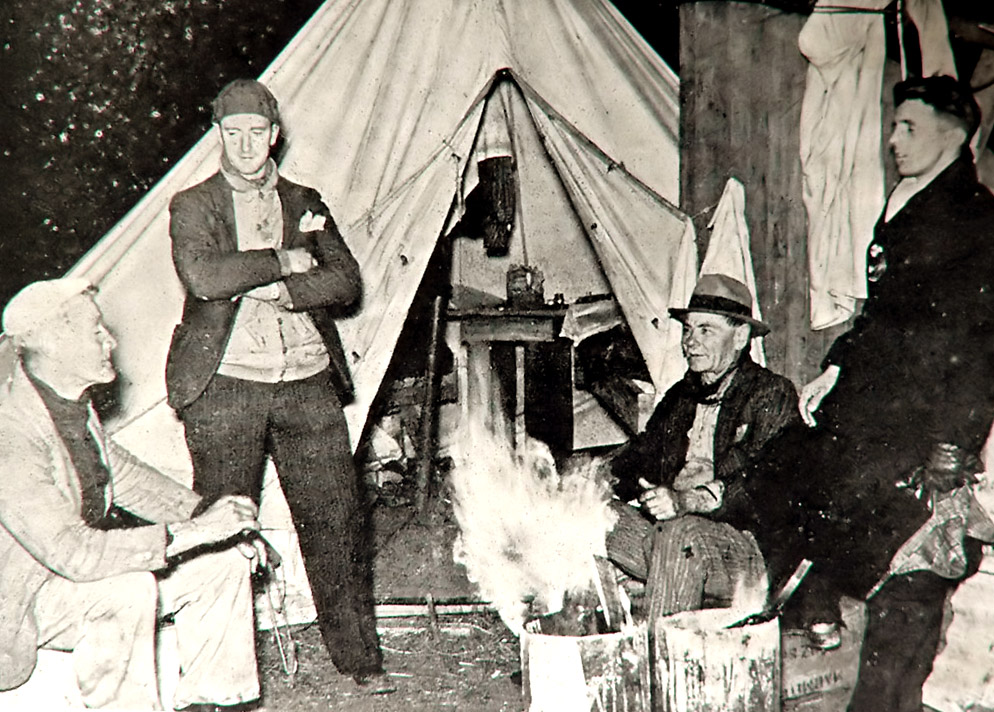

erecting the first of the new buildings. Some

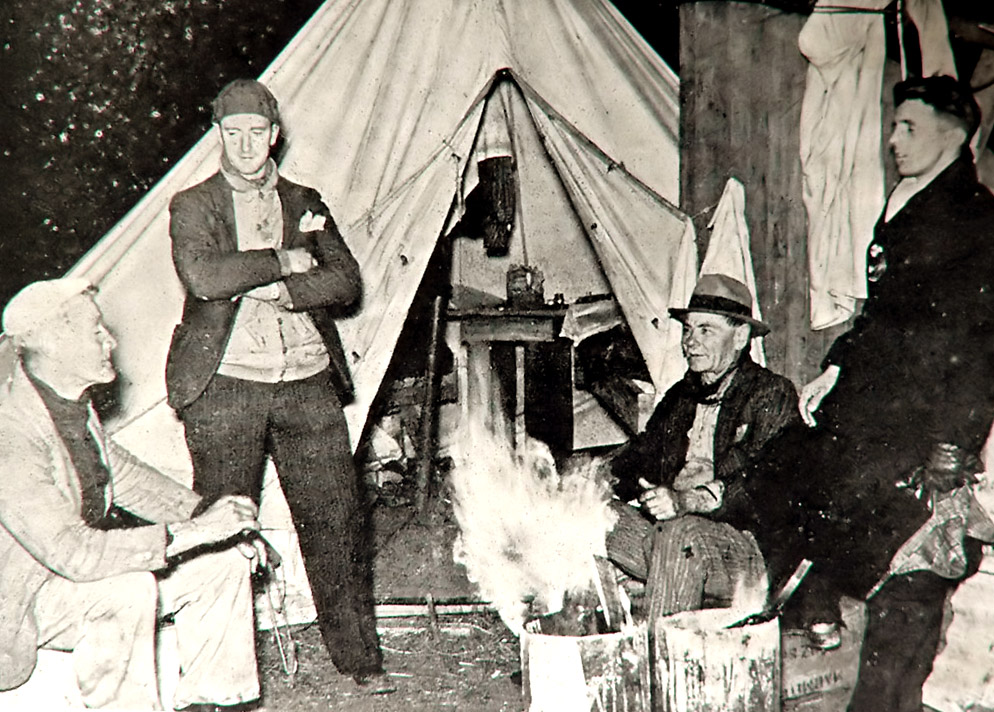

workers are accommodated

in the artillery’s 20 barrack buildings built a

couple of years previously, but 600 of

them are sleeping

in the army’s bell tents ( in mid-winter, in

Waiouru ! ) This is a great incentive to get

more weatherproof barrack rooms erected ASAP.

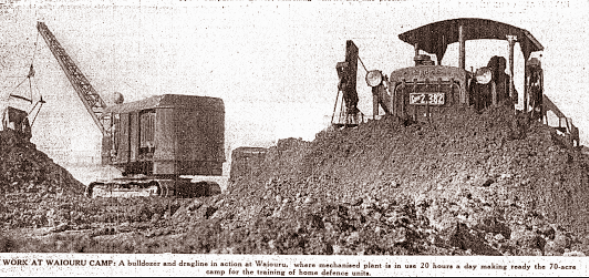

The work goes on 20 hours a day, in two 10-hour

shifts. At night the work is lit by dozens of kerosene

flares. The camp resounds with the banging of hundreds

of carpenters’ hammers and the roar of the 70

motor-trucks and 35 bulldozers, carry-alls and diggers

that are constantly on the move.Further afield, dozens

of gangs of other men are upgrading the narrow,

winding roads from Taihape, Turangi and Ohakune to

military standard. All the old wooden trestle bridges

on these roads are being replaced with heavy-duty

concrete ones.

1st

August 1940

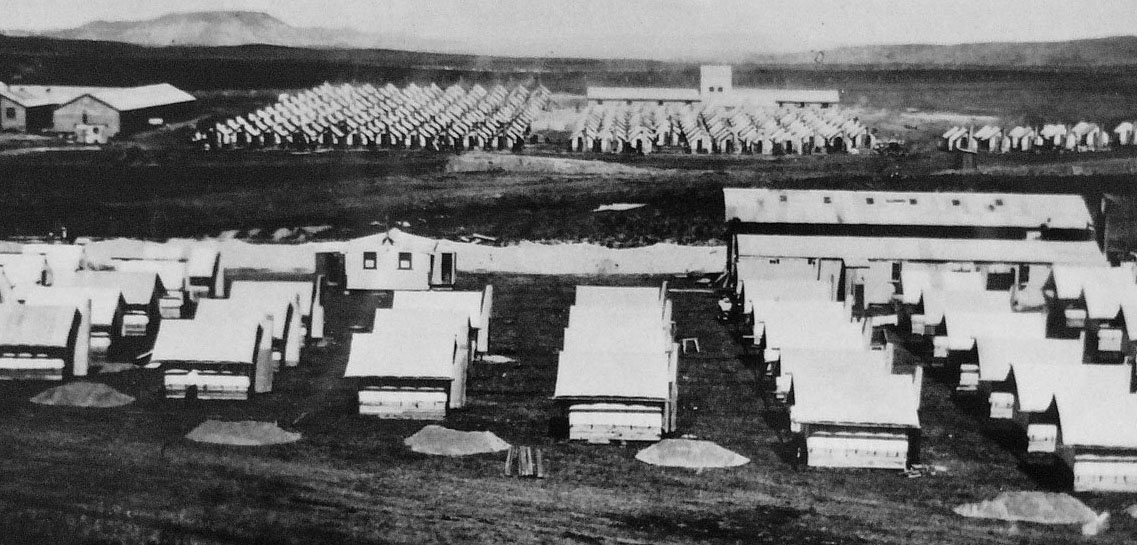

25,000

tons

of building materials are now on site. The

workmen have completed 40 buildings in their

first 30 days. They move into them as each one

is finished. Work continues on removing muddy

topsoil and filling swamps. A huge mound is

growing (between

today’s

wash stand and the Sgt’s Mess)

as

130,000 tons of swampy earth is removed and

replaced by the same amount of drained volcanic

sand and gravel. Eventually 60 hectares of firm,

level land will be created to site more than 360

buildings. Excavators remove another 40,000 tons

of soil to make a trench that diverts the

Waiouru stream around the camp site.

September 1940

An 180,000 litre reservoir is taking shape on what

will become known as Tank Hill. Two dams are being

built to feed it. 9 km of water mains are being

laid to distribute the water, and similar lengths

of stormwater and sewerage pipes. There are now

1,200 workers on site.

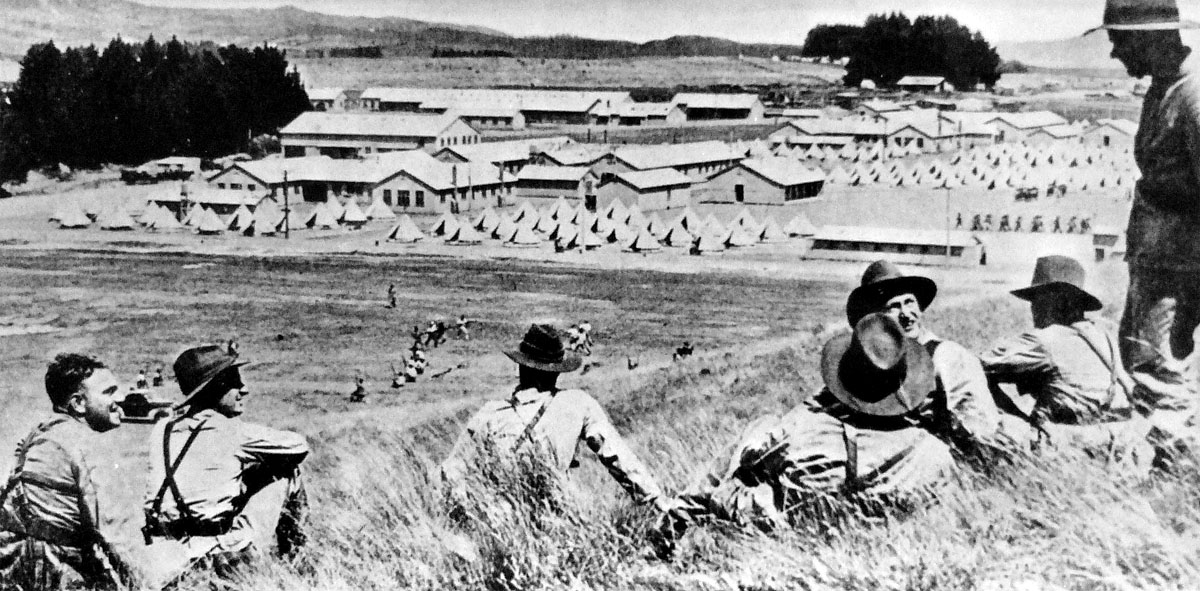

The First Echelon of 2NZEF arrive for

field training, sleeping under canvas in the snow.

October

1940

140

km of copper power cables have been strung up on 560 power

poles. The camp has been connected to the national grid

and the builders are now working under floodlights. A 550

KW diesel generating plant has also being installed should

the national grid be taken out by enemy action. From Tank

Hill we can see five bridges, 22 kilometres of streets and

40 km of gravel roads under construction in and around the

camp.

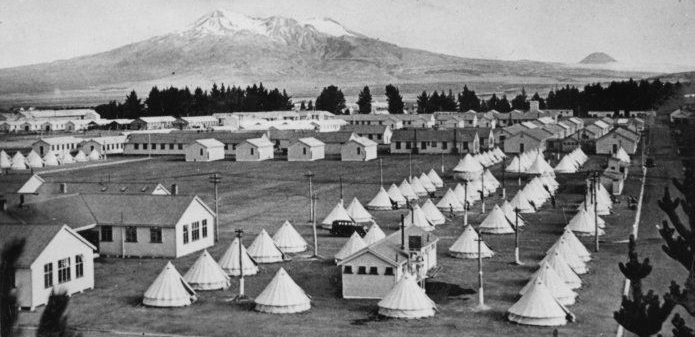

Wooden

PWD huts behind contractor’s’ tents (with

chimneys).

November

1940

The

workers

move from the barrack buildings to portable huts

sited just north of the camp. The

1st Field Regt NZ Arty arrive from

Rotorua. A branch railway line from Waiouru

Station to the quartermaster’s stores is

completed.

January 1941.

6 months

after starting, the workers have now completed their

240th building.

The

2nd Battalion

Hawkes Bay Regiment, 2nd

Battalion Wellington Regiment and 3rd

Battalion Auckland Regiment, as well as the

12th Field

Regiment NZ Arty arrive at the camp. There

are now over 7600 men in the camp, including 600

construction workers finishing off buildings,

tidying up, sealing parade grounds, erecting fences

and sowing grass-seed. Many of the soldiers

still have to sleep in bell tents (with electric

light and wooden floors), but facilities for cooking

and eating meals, for washing clothes, shaving,

showering, toileting and for recreation are superb.

There are hundreds of hot-water taps, scores of

flush toilets.

Feb

1941

The

1st Mounted Rifle Brigade arrives,

with 1500 horses. The horses are quartered in

lines near the present day Naval radio

transmitters. But by April the climate has

become too cold for many of them and in their

confined conditions 500 develop strangles, a

bacterial throat infection. They are moved

north by train to Ngaruawahia Camp.

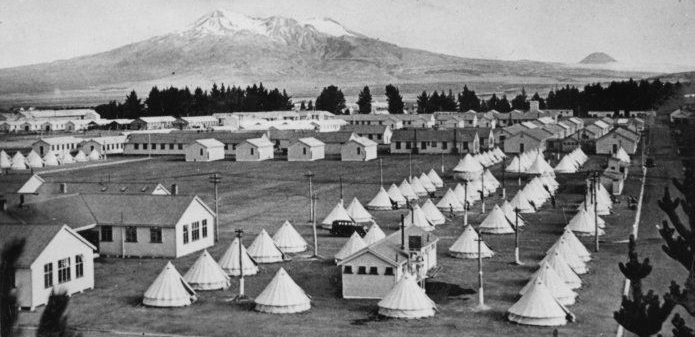

May 1941

The

camp

is finished. As well as barrack buildings for the

battalions and the camp HQ, there are two rifle

ranges, 30 explosives magazines, a motor garage, a

100-bed hospital, a dental clinic, a nurses home, a

1000-seat picture theatre, a fire station and five

recreation Huts, each with a café, lounge, library,

billiard saloon, concert hall and letter-writing

room.

But there are no bars. Most of the soldiers are

17-year olds, and the drinking age is 21. The camp is

dry. So the boys write letters instead: approximately

60,000 sheets of paper and 30,000 envelopes are issued

over one three-day period.

Every day the camp bakery with gigantic twin ovens is

turning out thousands of loaves and the butchery is

cutting up tons of meat, while warehouses at the end

of the railway siding are distributing dry foodstuffs,

clothing, ammunition, petrol, coal and

thousand-and-one other commodities. Opposite them,

near the main gate, is the guard house, with cells and

a prophylactic building nearby, for soldiers who have

over-indulged in various ways while on leave.

The only

inadequacy is Waiouru’s tiny post and telegraph

office, which has to deal with letters, parcels,

telegrams, toll calls and savings accounts of 7000

soldiers (There were no courier vans, emails,

cellphones or eftpos cards then), and the PWD workers

are now completing a much bigger Post Office.

300,000

lengths of timber

50,000 sheets of galvanized iron

17,000 sheets of glass

1,600

rolls of tar-paper

and

300 tons of nails |

Winter 1941 - Feeding the Troops

All these active young men in the camp, more than 7000 of

them, need feeding. The catering staff has to provide

150,000 meals every week on a budget for food of £4300 a

week (the average weekly wage in New Zealand is about £4

for men and £2

for women).

Each week the men in the camp consume 12 tons of bread, 18

tons of potatoes, 20 tons of meat, 9 tons of vegetables,

20,000 litres of milk, 2 tons of cheese, 3 tons of jam, 3

tons of butter, 2 tons of flour, 2 tons of rolled oats and

680 kilos of tea leaves.

However there is some difficulty in turning good food into

good meals: there are many complaints at first, the

regular force soldiers appointed to do the cooking do not

have the experience of preparing such large volumes of

food. The Territorial regiments provide their own cooks,

and some, but not all, were up to standard. An army school

of cookery is set up to remedy matters, but still there

are complaints.

War Profiteers

Skilled cooks need plentiful supplies of top-quality food,

and in April 1941 an investigative reporter from “The

Truth” newspaper discovers that war profiteers in Auckland

had obtained a monopoly on re-selling fruit and

vegetables, and are exploiting the soldiers by charging

high prices. In the autumn of 1941 there are huge

surpluses of tomatoes and apples, but almost none get to

Waiouru. Instead the soldiers have to make do with tinned

fruit from Australia.

There are paddocks full of cabbages and caulifowers just

down the road from Waiouru. But the monopolists are buying

them all and taking them by rail in non-refrigerated

wagons to the market at Auckland, before they are sold at

a big mark-up and brought back, well past their best, to

Waiouru.

But conditions in Waiouru are better than in Australian

camps. An army instructor who had been posted to several

Australian camps spoke of having no hot water, primitive

latrines, sleeping on mattresses on the floor, and only

limited quantities of food. “ When I came to Waiouru, I

thought I was in a first-class hotel,” he reported.

Source

Croom, F.G. 1941, The History of the Waiouru Military

Camp.

(typed manuscript - Waiouru Museum library)

|