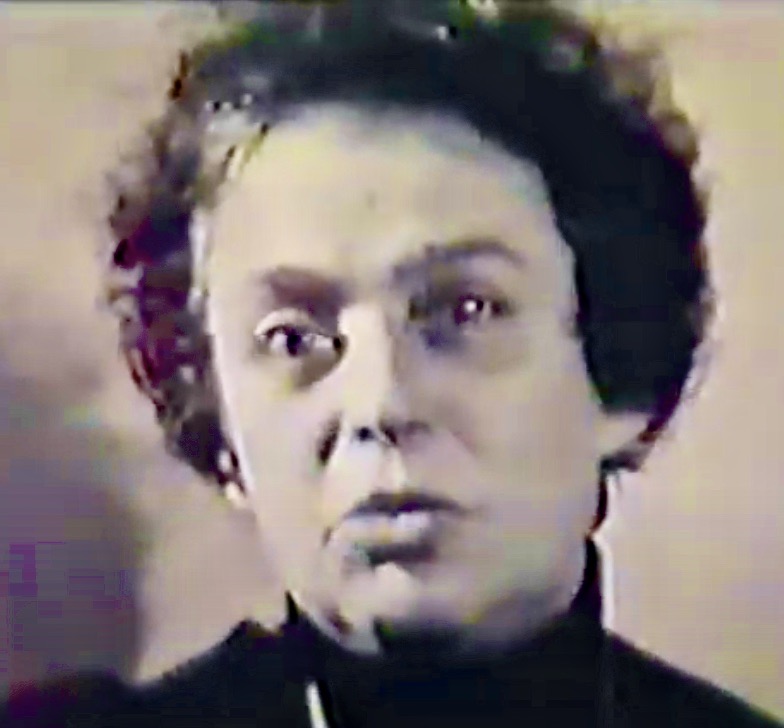

| Born in Germany in 22 February 1920, she was a survivor of the Gestapo, a social worker and songwriter, a worker for the postwar East London homeless and early influence on Paul Simon. After her third marriage, to instrument technician Stephen (Simcha) Delft, they moved to New Zealand. She died in Levin, New Zealand, 19 June 2003.  Judith Piepe in London, 1965 Judith Maria Sternberg was the grand-daughter of an ultra rich German Jewish financier - "My grandmother had her own private train" - and daughter of a left-wing political theorist. In 1933, when she was only 13, her father escaped the Nazis and she was imprisoned in Berlin for 3 months, tortured there by Nazis trying to find him. For most of the 1930s, with all of her relatives gone to the USA or to concentration camps, she wandered Europe, before escaping to Switzerland, then to England on the eve of WW2. "I

could have had very expensive psychotherapy in Switzerland

to take my mind away from all that, but I did a PhD in

philology there instead."

(JD to JA 1982)

She had one daughter, Ariel, by her second marriage to Tony Piepe in 1951. In England, her philology studies led her to High Anglican Christianity, and in the sixties and seventies, as a motherly social worker for St. Ann's parish in Soho, whose specialty was ministering to the homeless, she presided over by soon-to-become famous young guitar geniuses and singer-songwriters who could be heard for a few pence in folk cellars and church crypts. "Many

of boys on the street had to prostitute themselves to air

force officers just to get a meal and shelter from the

rain for the night, so I took them to convents to give

them a refuge there. But the Mother Superiors turned us

away; "The Sisters might want to sleep with them," and

when I took them to monasteries, I got the same refusal. "The

Brothers might want to sleep with them."

"So they ended up sleeping on mattresses on the floor of my flat - and the young song-writers did too - they were the poets and prophets of our times. After Paulie and Artie made it big in the USA with their "Troubled Waters" album, CBC brought them back for a performance at the Albert Hall, and booked them into the Hilton. But that night they turned up at the door of my flat; "If we're in London, we couldn't sleep anywhere but at home" they said. (JD to JA 1982) Piepe always said her fondness for these lost ones came from having wandered through Europe as a stateless person in the years before her arrival to the UK. She kept open house at her home at 6 Dellow House in Cable Street, East London, for almost any folkie who needed a place to crash.

Dellow

House

"I was running a come-all-ye in the crypt when this American boy came up and asked if he could sing. I had never heard him sing before, so I held up one finger and told him to do one song, then look at me. If he was good enough I would hold up two fingers to indicated he could sing another. But it was so good that when Paulie finished it I went like this. (she waved 10 fingers in the air) He could sing as many as he wanted to!" (JD to JA 1982) A lot of talented people ended up crashing in Judith’s flat during the 1960s, but once Paul came through the door in 1965, it didn’t take long for them all to realize who was their den-mother’s favorite. The day Paul told Piepe he’d be delighted to move in, she knocked on Al Stewart’s door and told him he had to move into the smaller, darker room on the same hallway. Even Piepe’s eleven-year-old daughter, Ariel, who lived with

her father in Southsea, could tell that Paul outranked her in

her mother’s eyes. “He was the favored child, he got all the

love and attention,” she says. Tempted to hate the interloper

for taking her place, the girl decided instead to follow her

mother under Paul’s spell. “If I was going to square up in my

own life with her, somehow he had to be worth it.” "He

recorded it in a little studio that usually recorded

violin solos. There was only one microphone, hanging

from the ceiling, and when Paulie recorded 'Sounds of

Silence' he stood on an apple box and stamped his foot to

get the echo sound."

(JD to JA 1982)

J  udith

wrote the notes on most of the songs, and also the foreword for

a printed songbook of the same title, in which she said: udith

wrote the notes on most of the songs, and also the foreword for

a printed songbook of the same title, in which she said: I

consider Paul Simon to be particularly significant because

of the wide range of his songs, his intellectual and

emotional approach give them an appeal to far more than

just a narrow section of the population.

Paul Simon's songs are personal and individual, the expression of his own thoughts and feelings, hopes and fears, problems and frustrations of our time, of his generation. In speaking for his generation he says what others feel but cannot find the words to say, and in doing so has a liberating and healing effect. Judith was a larger-than-life woman around whom legends accumulated. She said she drove ambulances for the Loyalists during the Spanish Civil War, yet in the 60s, told an acquaintance she couldn't drive. She was said to have worked for British political intelligence during the early days of the war, but told me she spent WW2 doing a PhD in philology. Even her birthplace was in doubt. She was very proud that she was a "Schlesian", born in Silesia, then part of Prussia, now Poland, in 1920. Yet she spoke German with a Berlin accent, and her daughter maintains she was born in the German capital. Her mother was said to have been a French gypsy; not so, say others, she was a well-known Jewish intellectual and art dealer. She said very little about her father, which was also strange, since he was an esteemed Marxist economist who had exchanged polemics with Trotsky and ended his days in the United States, where he became a member of Roosevelt's "kitchen cabinet" and was a respected contributor to learned journals like The Nation. After acquiring British citizenship, she never lost her charming Mittel Europe accent. Although her father was Jewish and she was brought up an atheist, she converted to Christianity (High Anglican because she loved the ritual, and was not a rigid as Catholic church). Working for St Anne's Church in Soho, she asked her musician and singer-songwriter friends to play in the crypt there, creating what was in effect one of the country's first folk clubs to have its own premises. Three members of that Soho crowd, Peter Bellamy, Heather Wood and Royston Wood, under the name Young Tradition, recorded Judith's song "The Hungry Child" on their album So Cheerfully Round, in 1967. A young child to its mother ran and then it started crying, Mother I'm hungry mother dear give me bread or I'll be dying. Wait my child; wait my child, Tomorrow we'll be ploughing. Now when the field it had been ploughed the young child started crying, Mother I'm hungry mother dear give me bread or I'll be dying. Wait my child; wait my child, Tomorrow we'll be sowing. Now when the field it had been sown the young child started crying, Mother I'm hungry mother dear give me bread or I'll be dying. Wait my child; wait my child, Tomorrow we'll be reaping. Now when the field it had been reaped the young child started crying, Mother I'm hungry mother dear give me bread or I'll be dying. Wait my child; wait my child, Tomorrow we'll be threshing. Now when the wheat it had been threshed the young child started crying, Mother I'm hungry mother dear give me bread or I'll be dying. Wait my child wait my child, Tomorrow we'll be grinding. Now when the wheat it had been ground the young child started crying, Mother I'm hungry mother dear give me bread or I'll be dying. Wait my child: wait my child we'll be baking. Now when the bread was warm in the oven the child lay cold in his coffin. (Judith

Piepe)

This was written down and shown to one of "those people who knew traditional songs." He said it must be rural 1700s, and after he was told the truth, he was heard of no more. In the winter of 1969, the St Anne's crypt became a regular night shelter for the homeless and developed into the charity Centrepoint, taking its name satirically from the nearby office tower block at the top of Charing Cross Road, whose owners found it more cost-effective to maintain it empty. Judith met and became the partner of Stephen (later Simcha) Delft, a song-writer, audio technician, guitar builder and repairer. They married in the summer of 1981 and emigrated to New Zealand the following year. She became very frail in her later years and was taken into a rest home in 1998. My personal memories of Judith by John Archer Judith judged a folk-songwriters competition at a folk festival in Palmerston North in 1982 and afterwards she invited me to come and stay with her for the weekend so she could help me polish my songs. In England she had given all her money to waifs and strays, so her beloved Paulie, Paul Simon, had paid for her and Stephen to move around the world to an elegantly landscaped new housing estate in Upper Hutt, beneath the the wooded Rimutaka Ranges. The Rimutakas were so like the mountains where her grandparents had lived. “My

grandparents financed both sides of the Franco-Prussian

war. My grand-mother was so rich she had her own train.

She would send me off with two servants to a toy shop and

I could choose any things I wanted.”

They also reminded her of a fairy-tale ride to her grandparents' alpine castle when she was the same age. "They

tied a tag on my lapel and gave me to the conductor on an

express train at the station. Later he handed me over to

the guard of a little train heading up a valley. It

stopped a station and I was given to the station master

who lifted me up into a wicker basket hanging from the

side of a big white horse, and my bag and some mail in a

basket on the other side. The horse then set off, all by

itself, up a track through the trees until it came to the

gates of a castle, where a groom came out and took me

down.”

"Upper

Hutt is warmer than London, the suburban rail units can

whip us into the middle of Wellington (New

Zealand's capital city) in

half an hour, and any London musician who wants Stephen to

repair their instrument can airfreight here within a

couple of days."

Judith and Steven's nouveau-riche neighbours in 1980s Upper Hutt, on immaculately landscaped sections surrounded by wooden fences painted “redwood brown” and with trophy cars parked on their driveways, were delighted when they heard that icons of the London music scene were moving into their street. But when I arrived at the Delft house I found the front of the section enclosed by high wire-netting, a goose wandering through the dandelions, gorse, and long grass, a truckload of rough timber slabs dumped on the driveway, and their wooden fence painted white.... “....so Stephen can get enough light in his workshop in the garage downstairs.”

“Everything was artificial here, so we transplanted bushes

(pine wildings and gorse!)

from the hillside, and let the grass grow long so we

could enjoy the pretty dandelion and daisy flowers. That

load of slabs was given to us by a Maori worker without

money, whose guitar Stephen repaired."

"It is different from London here. I was discussing spirituality in songs with a Mongrel Mob member last month. The neighbours complained about the grass getting long, so we got Gos the goose to eat it. Now they complain even more about the Maori visitors here, but that means nothing to me; I’ve been tortured by the Gestapo!” So when I came home, I wrote this portrait of her, through the eyes of her poncy and increasing hysterical neighbour. When his Alsatian had left dog poos on Judith's overgrown lawn, she had let him know she would trap it in a cage and dye its fur pink. Those people next door,

why their lawn’s never cut

And they once chucked a rock at our Rover, poor pup “Ged in off the road there, yer dumb mongrel mutt Do you want to get bloody run over!" To get their grass grazed, they’ve got Gos the goose He’s a footpath-polluting old sinner, no use And he chases our dog every time he gets loose He wants Pate de Rover for dinner And that fence painted

white, it’s just the last straw

It’s dragging the neighbourhood down That fence painted white, it’s just the last straw It’s dragging the neighbourhood down If their fences were brown and their visitors white I’d give them a ride to the station, too right But they bring round those bungas, the wife’s scared at night We’re buying another Alsatian! And that fence painted

white, it’s just the last straw

It’s dragging the neighbourhood down That fence painted white, it’s just the last straw It’s dragging the neighbourhood down. Simcha, and Hartley Peavy's $10 commercial sample.Stephen (later Simcha) was amazing too. In 1987 I was making a trial recording of my songs at Upper Hutt on his 4-track tape recorder. "Sticky Bun needs a Sousaphone in the background," I commented to Stephen.The next morning I woke to hear my track of Sticky Bun Rag being played at a slower speed, and Stephen playing along "Dum. Dum. Dum." on a double bass. Then I heard the song being played at the correct speed, and magically, there was a Sousaphone in the background going "Poom, poom, poom." Judith told me he had often been hired at Abbey Road studios in the 60s and 70s to do similar feats. "They could hire a whole busload of classical musicians," she told me. "Or they could get Stephen." He was undoubtedly Europe's top instrument technician, whether repairing a North African oud to restore its authentic sound, engineering a sound-track, adjusting the wiring circuit in a valve amplifier to enhance its reverb, or designing an innovative pick-up. There's so much more to tell; a house crammed with 50 different stringed instruments from all round the world - and a bear suit that Paul Simon's girlfriend and muse, Kathy Chitty, made for the dancing bear in Stephen's band, "The Patriarch of Glastonbury - His Band."  And I mustn't forget the Peavey Rhythm Master (Commercial Sample - value $10 ! ) that young Hartley Peavey sent Stephen for writing very detailed technical reviews that helped him improve his products. Stephen explained how Hartley had designed the Rhythm Master for C&W band members who played at a different venues every night, replacing in just one box all the amps, mixers and tangle of cords that formerly they had had to deal with. Stephen handed me one of the lutes he had made, stuck a C-ducer microphone tape he had invented onto it, plugged the C-ducer into the Rhythm Master, twiddled its knobs, and magically, I found rich C&W guitar sounds were coming out of the Peavey when I strummed a few chords on the lute. So I drew on every C&W stereotype I knew, and started singing about a Texan ranch-hand's love songs to a girl who couldn't hear him until he got a Peavey. "Frarm the moment Ah farst

sar yah, in thart Lone Starr burgerr barr..."

"No,

no," said Judith, "Make

it a song from your own experience, about a New Zealand

boy doing work you hef done."

I had worked as rousie in a shearing gang for a couple of weeks,

so I concocted this Kiwi send-up, full of C&W clichés (and a

few double entendres) as a tribute to Judith and Stephen. He was

the president of the Hutt Valley Hedgehog Preservation Society. From the moment that I

saw you

In that Taihape shearing gang, I loved the way you moved as you handled each fleece And I loved the songs you sang. As I bent over my handpiece, and dragged another sheep

from the pen

In the midst of the roar of that woolshed floor I could hear you again and again. Chorus And I wanted to say I

love you

but I couldn't find a way I wanted to say I want to be with you for ever and a day But the dogs and the sheep and the shearing machines Made my words seem only dreams I wanted to say I love you but the noise got in the way. Well I drove down to Mangamahu Borrowed my mothers's guitar It was an F-hole plywood Antoria - shoved it into the boot of my car Back in the shed at Taihape I strummed it at smoko time But with the noise from the pens And the yarning of the men You never noticed those songs of mine Chorus And I wanted to say I love

you

but the noise got in the way I wanted to say I want to be with you for ever and a day But the noise in the shed took the words from my head Though I strummed til my fingers bled I wanted to say I love you but the noise got in the way. In the Taihape pub we were having a beer When I saw a guitar with an amp So I said "Gidday mate, c'n I've a go with y'r gear?" He said "Cracker son, go f'r it champ, Its a real little beauty I picked up in the States It's made by some joker called Sears (Robuck) Just give it boot if it crackles or spits Its been that way this last 20 years." So I tried to play I

love you

But the noise got in the way I wanted to say I want to be with zzzt For ever and a day But that bizzz threw a fit! And though I gave it a kick I was drowned out in crackles and spits I tried to zhhh I love gwikk But the gharrr got in the gekk. Bridge Well it was raining the night I drove home to Mum to tell her of my courtship disaster We drank kiwifruit wine and she said "Listen son, Get a Peavey Rhythm Master." In Hedgehog Valley this

technical bloke

had a Peavey that was real user friendly I chainsawed his firewood and we did a deal And his Peavey he happily lent me Back in Taihape when I couldn't find you I put the Peavey on a pick-up truck I started singing and playing in Memorial Square And I hoped for a change in my luck. And when I tried to play I love you The words came clear as day I was able to say I want to be with you For ever and a day My guitar and my mike and my rhythm machine Were sounding sweet and clear and clean I was able to say I love you When I did it the Peavey way. (transpose

key up)

Then out of the night you came running You plugged yourself in beside me And on the back of that truck we drew a big crowd with our woolshed harmon-ee-ee-ey And now we're a modern duo And soon we will be three And in honour of the amp that made it come true We're going to call our child Pe-e-ea-veeey! And a final piece of Judith’s song-writing advice – “Don’t

tell the audience what happened; make them EXPERIENCE it.

And pronounce the final consonant in each line clearly!” |